Alexandra Waierstall’s work ‘A line, a gaze, a horizon’ premiered at the Cyprus Choreography Platform in November of 2020. Inspired by the overwhelming shift to digitally screening dance in 2020, Waierstall’s work explores the effects of the camera and screened dance on live choreography. With a Terpischore grant from the Cultural Services of the Ministry of Education and Culture, Waierstall extended the work into a full-evening performance, which premiered in September of 2022 to music by Hauschka and Stavros Gasparatos. The piece was originally conceived for three performers, Arianna Marcoulides, Rania Glymitsa, and Savvas Baltzis who is simultaneously the videographer. The 2022 version featured Ying Yun Chen as an additional dancer. In a recent interview, Waierstall, a Cypriot-German choreographer who resides in Germany, explained that the process and choice of dancers for the original production in 2020 was affected by logistics of travel, which was halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns. Recording of spoken word written and performed by Waierstall, which combines instructions for the dancers with poetry, accompanies and guides the piece and informs this essay. This article examines the work’s structures and its implications, by presenting a description of the work and a few screenshots from a video of the performance. The latter part of the essay presents an analysis of the structures of the piece and the effect of screendance on live performance, in terms of the compositional methods offered by the use and effects of the camera, the exploration of space and site, and the phenomenological experience offered by the work.

I have been following Waierstall’s trajectory as a choreographer from the beginning of her career, which developed in Cyprus and Germany over the last twenty years. Her works are characterised by minimal and stark visual representation where movement takes the lead role. Always working with stunning dancers, Waierstall seems to gently guide them into her approach to moving without forcefully dictating her style. The movement in her works has a particularly malleable quality – it feels like air trapped under a parachute. Waierstall (2022) explains that her movement choices are rooted in ‘this relationship of the front and the back breaking the frontal line … so the back speaks equally as the front.’ The work discussed here was created entirely online with the choreographer sending a specific script to the local dancers and the videographer with all of whom she had a previous working relationship. Waierstall (2022) describes her dance making as based on trust and guided by the principle of ‘it’s not about me telling you what to do. It’s about what we agree to do.’ The dancers were given guidelines for movement but not specific sequences or steps, however she guided them with ‘very specific ways of how they [dancers] attend to … the space and how they attend to their body’ (Waierstall 2022). The performers, with the choreographer’s guidance and clear physical anchors, created a work that follows her well-established aesthetic of quiet tension, calmness, and unexpected twists and spirals, which redirect the initiations of the movements and its vectors into surprising shapes.

A Line, A Gaze, A Horizon

This dance piece begins with a projection of a white light across the entire cyclorama. It is bright and hard to discern.

Oslo. Paris. Milan. Left arm rising three cm. Ball of the foot. Nicosia. Tokyo

Arianna Marcoulides enters the stark stage wearing a greyish blue tunic, leggings, and trainers. She begins to move according to the spoken instructions while an onscreen image begins to move to capture the backstage wall, the exposed side lights, and Marcoulides from the back, revealing a complex interplay between the live dancing and the live projection performed by Savvas Baltzis.

Marcoulides performs an expansive lift of the left arm whilst lifting her knee to take an exaggerated step backwards translating a simple step into an artistic statement. Videographer Baltzis appears stage left. Holding his camera, he creates a strong corporeal presence on stage establishing his role as a performer. As he moves towards Marcoulides, they form a physical and digital relationship. His motion causes the image of the dancer on screen to enlarge, exposing a simple filming technique of alternating the size of the body through the camera’s position. A new dance emerges from this shifting relationship between three subjects — the dancer on stage, projected image of the dancer on screen, and videographer with his cumbersome camera. Baltzis focuses on the camera and its view for the entire piece establishing his relationship with the dancers by negotiating with them purely through technological equipment. However, his physical presence and movement adds a crucial element to the choreography of bodies on stage.

The camera changes its angle. You can see me from behind

The relationship intensifies as Baltzis moves in closer allowing the screened image of Marcoulides to grow and overwhelm the scrim. He circles around her showing multiple perspectives of the same movement. The dim lighting catches the exposed skin of Marcoulides’s arms, neck, and partially covered face. But the image captured by the camera and projected onto the screen shows more detail, colour variation in the costume, and creases in the fabric, which offer texture to the kinaesthetic corporeality of the live presence on screen.

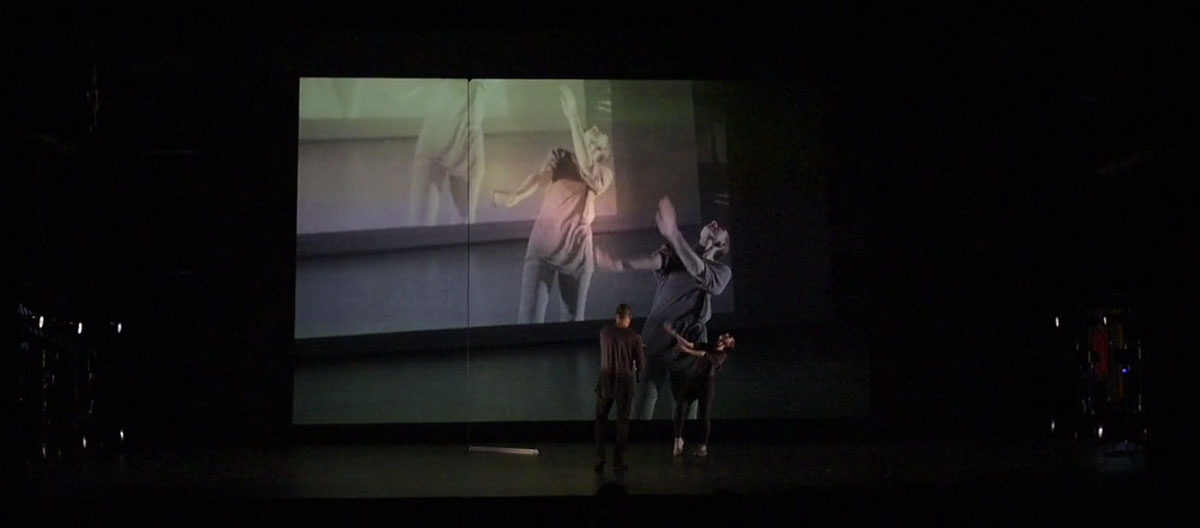

As he crouches in front of Marcoulides, the spectators see Baltzis’ back, a front view of Marcoulides shifting through a lunge and simultaneously a much larger, fragmented version of Marcoulides on screen (Figure 1). As the camera zooms out, the image is multiplied manifold creating a double mirror effect. Suddenly, the space fills with a chorus of dancers in perfect unison stemming from a single live performer and her partners — the camera and its handler (Figure 2). As Marcoulides performs a slow, eloquent turn and lifts her arms shifting into a large plie in second position, the videographer shifts sideways slightly, moving the placement of the screened replicas of the dancer.

Sometimes infrastructure, or structures we depend on shift…These can be natural things, like how much the sun shines and how much it rains

The videographer continues to spin, re-directing attention onto the auditorium to capture the audience.

Rania Glymitsa slowly rises out of her seat and pauses. Baltzis zooms in allowing her image to appear on screen alongside the audience members. Although, Marcoulides continues to dance on stage, the camera has re-organised the composition, allowing a view to the audience that the viewers would not be possible without the camera lens and its directed attention. The camera is commanding; it captures the auditorium placing the spectators on stage as a screened chorus backdrop.

Electricity… two meters…. three meters. Toronto. Malmo

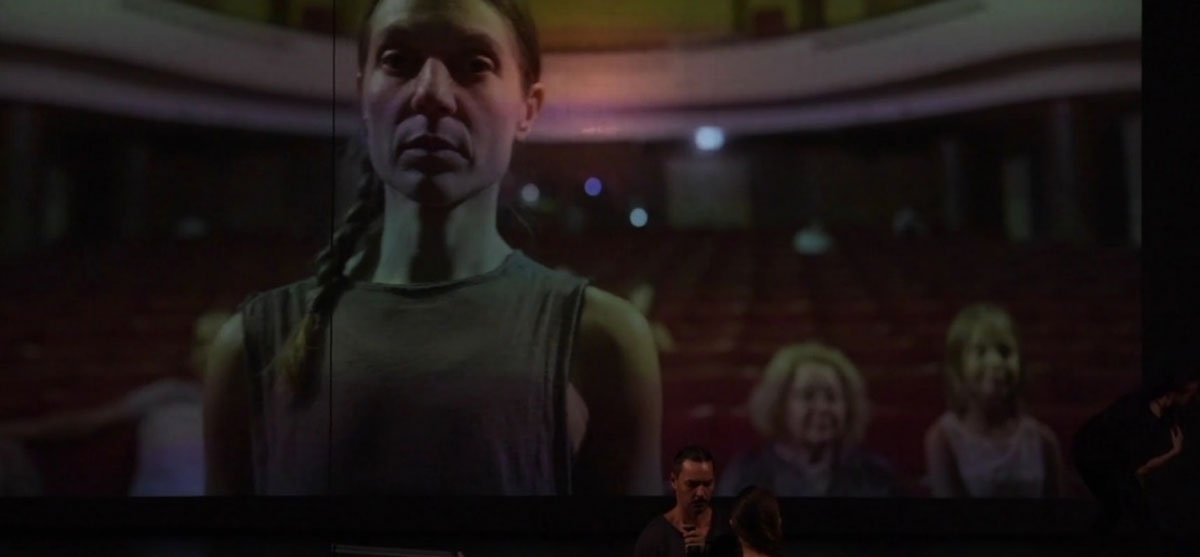

Glymitsa makes it out of the seats and looks directly at the camera forcing the audience to encounter details of her face and expressive eyes (Figure 3).

A line, horizon, a gaze into the infinite

Glymitsa steps on stage and proceeds to draw a line on the floor with white sticky tape. Baltzis captures her moving backwards, projecting an image on screen that amplifies the line of the tape. At the same time, the audience absorbs the complex visual design out of a simple arrangement of dancers and the videographer on stage and screen that shows various dimensions and perspectives multiple lines created on stage and screen with the white tape.

Ten, three, one and a half. I move slow and I hear my heart beating

The image of Marcoulides jumping on the spot enters the perspective of the camera. As Baltzis circles her with his camera, the audience is confronted with multiple images of a dancer bouncing slightly out of rhythmical sync that is a result of the technological manipulation. Marcoulides’ shoulder enters the camera frame and Glymitsa seen out focus. With the sharpening of the focus, Glymitsa also begins to jump.

Again. Two. Three. Five

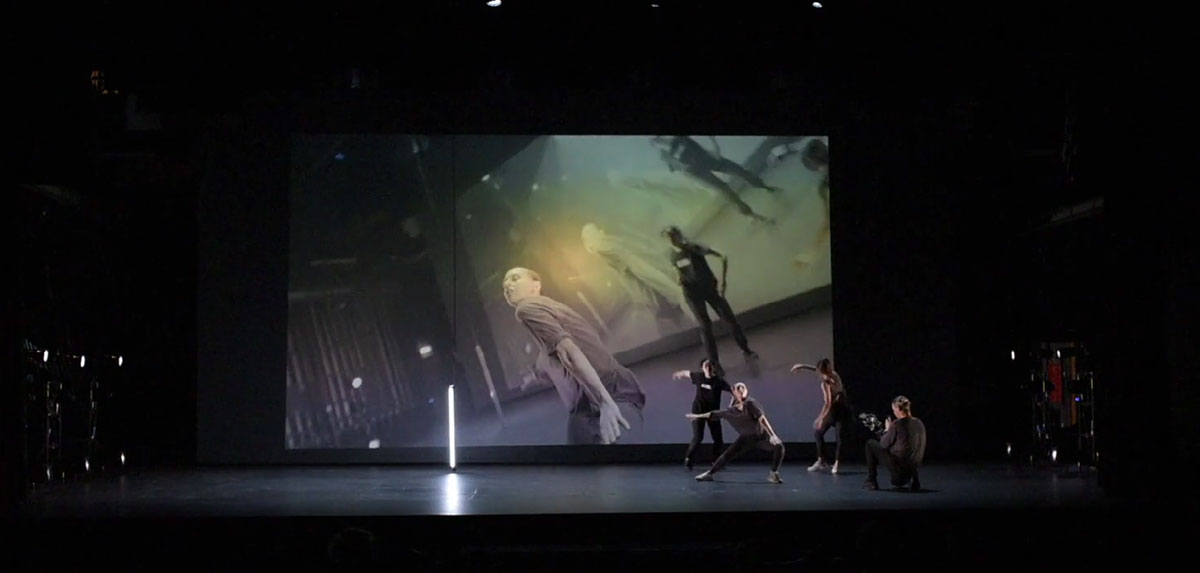

The two dancers continue to jump in sync but the camera work and the videographer’s placement and focus choices in relation to the dancers creates a digital landscape that distorts the simple jumps of the two dancers facing each other. They jump in perfect rhythmic unison creating a soundscore through their trainers hitting the floor and their laboured breathing. But the visual rhythm of their physical and aural movement is distorted. The screened version shows multiple renditions of the dancers at various tilted angles, creating a kaleidoscopic choreographic image (Figure 4).

Eight

One dancer halts her movement.

Seven

The other dancer joins her in stillness. The videographer straightens his camera to present multiple digital images of the couple facing each other on stage. Their screen magnifies their slightly staggered spatial relationship causing one of the dancers to appear much larger than the other and far further forward than what is perceptible in the live, material relationship.

There is a wild place, there is a wild place, not too far from here. This place wasn’t always so wild.

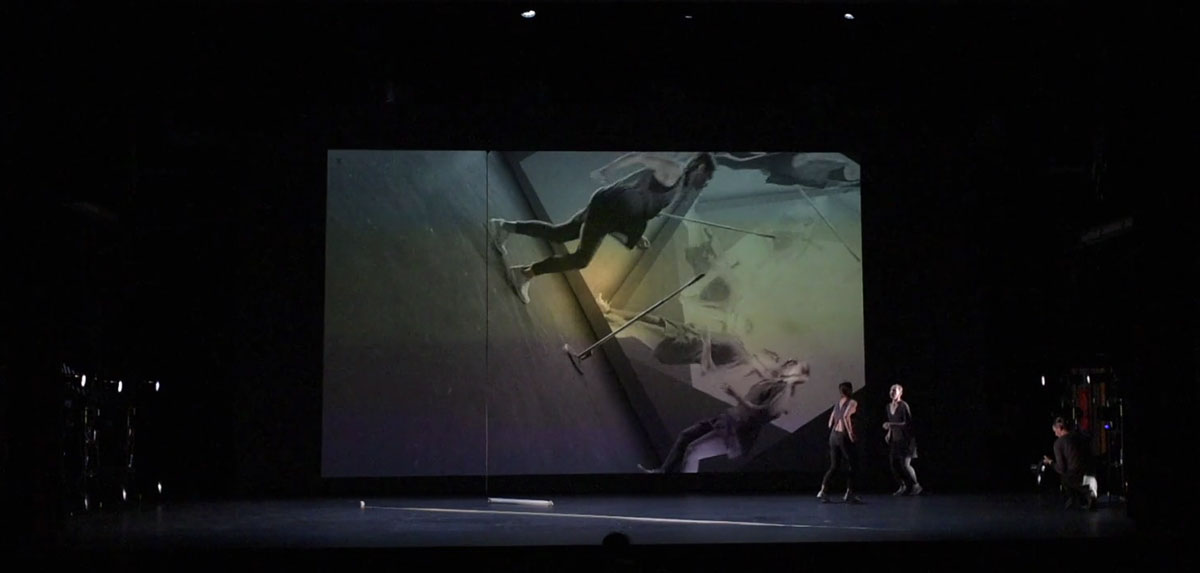

What proceeds is an homage to the theatre, its construction, and the possibilities of the camera in transcending physical limitations, opening perspectives, and offering new views. The videographer exposes the metallic structure and texture of the winding banister, the lines of ropes that lower and hold lighting rigs in place. Baltzis captures the ropes, metal rigs, electrical plugs and cables exposing the architectural structure as both mundane and magical. By reaching into this space of the theatre, hidden from the audience, and even performers, Waierstall calls on site-specificity; the theatre becomes integral to the work as explored through various camera perspectives. The two dancers re-enter the stage and Baltzis captures them from above using a classic dance on screen method of the overhead shot, which presents an alternate and impossible live view to the theatre audience of the two dancers performing on a stage divided by the white tape. The multidimensional experience of seeing movement invites a new kinaesthetic empathy — one of understanding the weight of movement of live dancers, and one of screened images which provides an alternative glimpse into the movement’s design.

My heart accelerates. I am four meters off the floor.

The dancers are transported onto a different site, as the videographer shifts to the overhead lighting bridge for the stage, making it seem like the performers simultaneously occupy the traditional stage setting and the theatre’s upper level. The camera’s movement travels the dance across sites, dimensions, and textures.

Baltzis descends the theatre stairs creating a backdrop of whirling architecture of the backstage theatre created by his view of the traveling camera. Baltzis returns to the lower level capturing the dancers again. His presence is palpable — hidden behind the camera’s monstrosity is an elegant dancer whose corporeality leads the piece. His sweat illuminates his physical labour similar to the dancers’ artistry.

The electricity goes off. Silence. Still. My feet now touch the ground. Water.

The sound of this place changed.

Three. Two. One

In the new version of the work, the audience is introduced to another dancer sitting in the front row. She walks towards Baltzis penetrating his space and causing him to move backwards. The close-up of her face overwhelms the screen while the two other dancers switch to a pedestrian mode to remove the tape.

Minimalist music begins as the dancer starts to move her arms. Baltzis captures her face. She performs simple gestures of touching her face. The choice to film this moment in an intense close-up gives the camera power and overwhelms the visual composition (Figure 5). Baltzis begins to circle Chen on stage offering a circular view of her body positioned in a single spot executing simple arm movements. The play of the camera and lights projects a rich visual dance composition on screen filled with sweeping movement despite the dancer’s stillness. The closeness of the camera captures the texture of her hair and realities of her skin in microscopic detail, bringing her physical existence in sharp focus that compliments and contrasts her actual corporeal presence. Baltzis settles in front of her and zooms out to show her body in relation to the auditorium. The projection on the screen asserts a powerful presence in relation to the static dancer’s body on stage.

The choreography culminates as the music switches to an electronic beat. Chen begins to draw from a vocabulary of sweeping curvilinear arms, interrupted by the movements of the back and head. Baltzis and Chen present a choreography of her stylised and his pedestrian movement, the camera, and various screened images that multiply and distort the dancer. The other dancers join in while Baltzis, through camera and editing, includes fragments of dancers, alternate perspectives of their movement, creating a moving backdrop that includes numerous screendance techniques, such as distortion, fragmentation, and multiplication (Figure 6). The dance exists in the interplay between the action on stage and the images on screen that would not be possible without the technology of the camera and digital streaming.

Finally, all performers depart the stage leaving a lone fluorescent light to sway. Eventually, that stops, and lighting technicians dismantle some of the lights from a lowered rig. Waierstall ends with exposure of technical staff, their input in the artistic process, and the baring of the technical aspects of a performance, adding another layer to her revelatory compositional process.

Live and Mediated Performance: Phenomenology in Motion

Waierstall’s multidisciplinary piece presents a visual and kinesthetic experience by showcasing live dance performance on stage, live choreography of the camera and screen, and an exploration of space and time afforded by this combination. Waierstall’s work is an experiment in visual and video art along with the experience of kinesthetic element of dancers moving on stage and screen. For the choreographer, the perspectives are many and complex, challenging the audience with a multi-faceted aesthetic experience. Waierstall provides an experience for the audience that is visual, cinematic, kinesthetic, and emotional that is in line with Anna Pakes notion that dance is ‘inevitably perspectival’ (2011, p. 34). The visual composition contains the architecture of the theatre, the choreography of bodies in space and on screen punctuated with the use of the white tape and the hanging light. The kinaesthetic element comes through the physical movements of the dancers, the videographer’s movement and directorial choices and the camera led movements on screen. The movement choices, structure, and scenery of the live bodies and screened choreography along with kinaesthetic perception of the dancers for the audience relates to Mark Franko’s idea that dance pairs ‘performer’s discourse of sensation with the spectator’s discourse of visual reception’ (Franko 2011, p.1). The audience has a sensory task to absorb the architecture of the stage, the hidden parts of the theatre including its industrial design and the auditorium, the composition of bodies on stage and on screen, the aural landscape of the spoken word and two very different musical compositions, and the corporeal manifestations of the dancers in two mediums.

The experience of watching screendance as opposed to a live performance may be critiqued according to Walter Benjamin’s idea that ‘even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be’ (Benjamin quoted in Rosenberg 2012, p. 22). Furthermore, Harmony Bench states that ‘the move from stage to screen has been criticized for abandoning precisely what makes live performance appealing: risk, spontaneity, ephemerality’ (Bench, 2006, p. 89), which Waierstall dispels with the immediacy of her work. Waierstall’s inclusion of live-action videodance in performance conceived for a proscenium theatre radically alters thinking around live and screened performances. The sense of responsiveness and immediacy is amplified with the spoken instructions which dancers seem to interpret in that moment creating an idea that choreography is materialised on stage in real time providing the excitement of a live performance and creation. Additionally, screendance is created in real time as the videographer makes choices on how to film and project the choreography.

Waierstall comments on screened dance and live performance by including both and thus deepening the understanding of both. The works recognises the lived experiences of the dancers in real time by presenting the digital and material interpretations of the dance. Olivieri powerfully argues for the power of screendance as a ‘way to translate the kinaesthetic exchanges of its makers … that brings us closer to understanding and valuing one another’s difference’ (2022, p. 180) through intellectual, emotional, and kinaesthetic responses of the performers and audiences to the work. Olivieri quotes the video dance maker Tim Glenn to illustrate the particularities of dance for the camera by saying that an experience of ‘adding motion to motion’ (Glenn in Olivieri 2022, p. 183) enhances the experience of dance. But Waierstall queries this relationship further as it is not clear if the dance is made for the camera, or the camera captures the dance and creates a new one containing its screened element, the choreography of the videographer, and the interaction between the live and mediated performance. The collaborative relationship between the choreographer, videographer, and dancers creates a visceral experience, which combines the material presence of the dancers and the videographer, the digital presence, and ephemeral experience.

Waierstall’s work showcases the complex relationship between the dancing body and technology that Rosenberg describes as a ‘collaborative, hybrid undertaking’ (2012, p. 1). Dance on screen shifts live performance to mediatised representation and the dance ‘is reduced to the smallest sum of its parts’ (Rosenberg 2012, p. 1). As demonstrated in the descriptions of the choreography above, each gesture is viewed in isolation allowing for a microscopical investigation of movement changing the way composition is conceived and viewed. The inclusion of dance on screen deepens the choreographic possibilities and viewing experience by adding an additional aspect to the work. The process of screendance and its (re)production is conceptual and physical as the camera and editing constructs the performance of the body. The camera and instant editing expand the body’s possibilities. Waierstall’s work supports Rosenberg’s (2012) idea that screen dance actually recorporealises the live event by doubling the experience of the performers’ (including the videographer’s) corporeality. In this case, Waierstall offers a live corporeal presence and a screened one that may accentuate and hyperbolize the experience of corporeality. The dancers’ and videographer’s corporeal presence accentuated by the screened presence of their dancing bodies makes the work visceral by doubling the impact.

She explores possibilities of composition with screened dance to create a more nuanced perception of materiality and ephemerality on stage with the combination of live and mediated live performance. Waierstall exposes some of the construction of the creative process by including the text with instructions for movement, live camera work that exposes the equipment, work of the operator, and instant editing, however, draws attention to the corporeality of the dancers as the key element in creation, presentation, and reception of the dance. The emphasis on corporeality sits at the core of this work as movement on stage and screen takes the leading role. The dancers engage in exploration of movement through structured improvisation making their physical presence visceral and conscious. The videographer’s actions and decisions on how to present the moving bodies on screen enhance the perception of choreography and, thus, draw more focused attention onto the corporeality of the dancers. Even in the section where the videographer travels to the top of the theatre, movement remains the protagonist. Whilst experiencing the architecture of the backstage space, which dances through the camera, the spectator knows that this is due Baltzis’ physical movement.

Prior to the actions taken by the dancers, initially in rehearsal and then on stage, instructions and score are simply ideas that require the corporeal efforts to create dance. As Waierstall exposes the structure, the script, and mechanics of choreography, she imbues the dancers with agency to communicate ideas with their physical subjectivity. Harmony Bench’s writing describes the process of performing choreography, the score, which is important to understanding the role of dancers in the performance of choreography as way to enliven dance as she states

‘Gestures, steps, moves, movement phrases, dance routines, somatic practices, choreographic scores: all of these exist as movement ideas that take shape through corporeal instantiation and interpretation. They travel contagiously and accrue affective weight and meaning as they travel across the bodies that come to perform them. Embodiment activates these objects’ (2020, p. 162).

It is the dancers moving that brings life to the score with their embodied response to the spoken word, camera, and space. This ties in with Blanco Borelli’s argument, which posits that dancing draws attention to corporeality as a political tool. She proposes that shifting the focus onto the body as a ‘real, living, meaning-making entity’ allows for an understanding of how subjects find and assert their agency with movement (Blanco Borelli 2015, p. 64), thus, Waierstall’s attention the moving body on stage and screen resulting out of the collaborative choreographic and filming process gives agency to the dancers. Without the presence of Marcoulides, Glymitsa, Chen, and Baltzis, the stage and screen would remain blank. They enliven the score as creative and originative collaborators.

The work creates a deep sensory experience for the audience by demanding a hyper-focus on corporeality of the live and screened bodies. Laura Marks (2000) explains that cinema, or in the case of Waierstall’s work screened dance, can invoke a sense of touch with haptic visuality defined as ‘the combination of tactile, kinaesthetic, and proprioceptive functions’ (2000, p. 162), which affects the surface and the inside of the spectators’ bodies. The emphasis on sound and movement, which is hyperbolised by the double presence on stage and on screen, draws attention to the corporeality of the body that forces the spectators to focus on the image and separate it from the narrative, therefore, turning it into a sensuous image that creates an emotional response by concentrating on the aesthetics by presenting close-ups and details of movement. Featuring live and screened dance simultaneously affirms Vivian Sobchack’ (2004) notion of carnal experience of film that is material, embodied, and aesthetic, thus, Waierstall’s inclusion of video dance on a stage affirms the potential of screen to present and enhance a kinaesthetic experience. The visceral experience of the work, rooted in the physical and screened presence of the dancing bodies is guided by Waierstall’s statement that ‘I think the skin is so vibrant in the work because I am really interested in the space where body meets the environment and how when I move … I shift space’ (Waierstall 2022). The combined experience of absorbing the dancing body through its live, material, three-dimensional presence and camera-led hyper-detailed offering of the dancing body on screen marks out ‘new territory for the haptic and totally immersive qualities of skin, musculature, and viscera’ (Quinlivan 2015, p. 67) that offers a more in-depth way to experience contemporary dance.

The work explores space, as an idea and concrete element through dancers’ movement choices, choreographic spatial patterns, and expansion of the proscenium theatre and digital spaces. In the interview, Waierstall explains that in her choreography she explores spatial patterns, which is an idea that is augmented with the inclusion of screendance. She explains that her intention for the dancers is to create a ‘dialogue with space around them’ and engage in deep listening of music in order to embrace the environment (Waierstall 2022). The choreography expands the idea of site-specificity of the theatre and screen within the traditional setting of a proscenium theatre. With the aid of the camera, various parts of the theatre usually hidden from the audience are used as places to perform and transport the performers. Furthermore, screendance places choreography in the site-specificity of media space making dance into a malleable, fluid, and digitally compatible corporeal text. In Waierstall’s piece the audience clearly sees the dancers in their physical location, yet by transporting dance onto a screen, performers become dissociated from a particular location, which allows access to a heightened, media-enabled mobility through camera work. Bench writes in relation to screendance that dancers ‘abstracted from built or natural environments that would situate their movement, bodies wander through space with an illusory freedom, unrestricted by physical or ideological barriers’ (2008, p. 37). Deeply grounded in their physical presence on stage or in the auditorium, the experience of watching dancers transported into new locations on screen provides a sense of wander to the audience.

The relationship between the camera, videographer, and the dancers

The live production of screened dance creates a heightened experience of the choreography and dancers’ corporeality as it alters the perception of the number of dancers audience watches, their size, and perspective. Introducing the camera into live performance offers new compositional possibilities and viewing experiences. Waierstall celebrates screendance by allowing the camera to participate, guide, and create a new dance. Her choice to bring screened dance to live performance bridges over the division between screened and live dance, concert, and popular dance. The camera alters the dance as an additional participant and acts as

‘a vehicle for capturing perspective. It is a channel, a crosser of space and time, and object-participant, a powerful observer, a director of attention, and a looking practitioner’ (Logan 2021, p. 259).

The camera is instrumental to dance on screen as it guides the gaze on to the body, providing a way of seeing that is particular to that instrument and vastly different to a viewing of a live performance. The microscopic technology of the camera allows for the audience to access details not available to the natural eye, such as the way the fabric textures react to the movements of the dancers. The spectator is invited to consider the details of the choreography, which play a significant role in the way ‘the filmic apparatus constructs a representation of the dancing body that can appeal to a mass audience’ (Dodds 2001, p. 37) and therefore can form a different relationship to the performance. The dancers are replicated, enlarged, multiplied by the camera, making the work feel much larger than a trio of dancers with a presence of a camera man.

The relationship between the videographer and the dancers is crucial to the effectiveness of Waierstall’s work. Screendance ‘integrates kinaesthetic and interpersonal exchanges between dancers and camera operators’ (Olivieri 2022, p. 182). This mechanism is amplified in Waierstall’s live filming, editing, and screening process and exposed for an audience to witness and process. Waierstall (2022) asserts the choreography of the camera was strictly scripted, however Baltzis’ movement, camera choices, and real live editing, which feel spontaneous are instrumental to the work. Waierstall confirms this when she states that ‘Savva succeeded in the way he films the work in the way that he films to work with the temperatures of the space so I could feel the heat of the body of Ying when he is close to her’ (2022). She explains that with the choreographic and filmic choices she felt that ‘I succeed in making the camera breathe’ (2022) acknowledging its power, importance and its role as a participant of the work that contributes to the visceral experience of the piece.

The powerful relationship between the dancer and videographer on stage is solidified during the section with Chen and Baltzis on stage. Chen’s minimal action, and the screened close-up illustrates Bella Balazs idea that ‘close-ups are often dramatic revelations of what is really happening under the surface of appearances’ (2003, p. 118). Rosenberg (2012) explains that the camera, with its telescopic and microscopic nature allow extend vision and create a deeper scope of awareness by drawing activities closer to the viewer. The close-up provides an opportunity to deepen the vision and focus on the intricate visual details. In this instance, as well as Glymitsa’s close-up, the screened close-up reveals what is often invisible in a proscenium theatre – the details of the dancer’s skin, face, hair, and subtle facial expressions. The close-up, along with the melancholic music, adds a tender and poetic dimension to the dance. It deepens the involvement of the audience and the emotional landscape. This technique extracts the face of the dancer from the stage action in an overwhelming visual presentation and thus, exemplifies Balazs statement that ‘close-ups can show us the very instant in which the general is transformed into particular’ (2003, p. 117). The close-up of Chen creates a visual and cognitive focus by transforming the openness of the stage into a concentrated presentation of her face.

Conclusion: Screened dance and its effect on live performance

The screen, and particularly the live feed in this work, adds another layer to the choreographic outcome. The camera work and its immediate projection alters the activity of the dancers and the choreography. The work skilfully combines the live performance of the dancers and videodance interpretation of the same choreography. As Rosenberg explains ‘method of apprehension (the screen) modifies the activity it inscribes (dance); in doing so it codifies a particular space of representation and, by extension, meaning’ (2012, p. 3). The inclusion of screened images of the dance does not serve as a trick or gimmick, but rather invites the audience to consider other meanings and perspectives of this dance. This dance examines and displays the mechanism of choreography and film making thus solidifying Randy Martin’s argument that dance is a ‘kinesthetic practice that puts on display the very conditions through which the body itself is mobilized’ (Martin in Bench 2020, p. 62). This choreography combines text, music, movement, filming, and screening assaulting the aesthetic sensibilities of the viewers and demanding a consideration of political meanings communicated. Waierstall bridges over the emotional attachment that may be created between the spectator and the corporeality of the performer in screendance by including both the live and recorded performance.

The choreography exists in the intersection between the movement of the dancers, the choreography of the videographer and the camera, and the projected images on screen. The work creates a quiet tension, captures the attention of the audience, and sustains the steady, sustained manner throughout the work. Although the work exposes the mechanisms of performance construction, it is poetic with words and movements. The work is deeply rooted in artistic sensibilities and pushes the dance form forward through use of technology. Waierstall’s choreography acknowledges the material and ephemeral characteristics of dance whereby the screen acts as a ‘receptor of an otherwise ephemeral image, and which reifies that image in the process of receiving it’ (Rosenberg 2012, p. 16). Through the collaborative effort of the choreographer, dancers, videographer, composers, and lighting designer and technicians, the dance transform from abstract ideas to a practical presentation and in turn ‘abstract choreographic structures, or mental images of movement’ that function as ideas ‘materially transform the bodies that carry, express, and transmit them and link those bodies to all the others who share a gestural or movement vocabulary’ (Bench 2020, p. 162). The embodied sensation of dance movement, use of breath, and material presence of the body experienced live and on screen creates a visual, aural, and haptic experience for the audience to experience corporeality (Quinlivan 2015).

Waierstall’s work explores relationship between live performance and the use of mediated image in dance by presenting dance in both of these conditions. In Waierstall’s work the combination of live performance and a performance conceived for screen offers a potential to create intimacy with the viewer by providing the real time and the screen altered experience of the choreography, which may present a more detailed, focused, and enlarged experience of movement. In the dance piece, the inclusion of live performance along with screened dancing and instructional texts, deconstructs choreography allowing the audience multiple access points into the performance. The screendance methodologies draw attention to the details of the movement and choreographic possibilities afforded by the camera providing a deeper insight into the performance. By including the process of filming dance whilst projecting it, the choreographer exposes the process of making videodance, the movement of the videographer, the apparatus, and immediate directorial and editing decision making that amplifies movement and its possibilities. Screendance in Waierstall’s piece simultaneously offers a documentation of performed movement and a subsequent treatment through the editing process. Additionally, the use of live streamed screendance extends choreographic possibilities with alternate perspectives of the dancing body, exploration of space and time, and a new sense of intimacy. The combination of live dance with its emphasis on corporeality of the dancers and the possibilities of screened dance alter the viewing experience that becomes material, embodied, and aesthetic.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Author Information

Dara Milovanovic is an Associate Professor of Dance and Head of the Department of Music and Dance at University of Nicosia. Dara holds a PhD in Dance Studies from Kingston University London, UK. Her scholarship appears in books such Perspectives on American Dance. The Twentieth Century and Fifty Contemporary Choreographers: Third Edition, as well as academic journals such as the Peephole Journal, Dance Research, Dance Education in Practice, and International Screendance Journal.

References

Balazs, Bela (2003) The Close Up and the Face of Man. The Visual Turn: Classical Film Theory and Art History. Dalle Vache, Angela (Ed.) Rutdgers University Press.

Bench, H. (2008) Media and the No-place of Dance. Forum Modernes Theater, 23: 37–47.

Bench, H. (2020) Perpetual Motion: Dance, Digital Cultures, and the Common. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5749/9781452962627

Blanco Borelli, Melissa (2015) Hip Work: Undoing the Tragic Mulata. In: Gonzales, A. & DeFrantz, T. (eds). Black Performance Theory. Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 63–84. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11cvzpk.9

Dodds, S. (2001) Dance on screen: genres and media from Hollywood to experimental art. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Logan, Kathryn. (2021) Considering the Power of the Camera in a Post-Pandemic Era of Screendance. The International Screendance Journal, 12. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v12i0.8303

Marks, Laura U. (2000) The Skin of film: Intercultural cinema, embodiment, and the senses. Durham and London: Duke University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1198x4c

Olivieri, Alexander Petit. (2022) Kinesthetic Exchanges between Cinematographers and Dancers: A Series of Screendance Interviews. The International Screendance Journal, 13. DOI: http://doi.org/10.18061/ijsd.v13i1.8768

Pakes, A. (2011) Phenomenology and dance: Husserlian meditations. Dance Research Journal, 43(2): 33–49. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767711000040

Quinlivan, Davina (2015) On how Queer Cinema might feel. MSMI, 9(1): 63–76. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3828/msmi.2015.3

Rosenberg, D. (2012) Screendance: inscribing the ephemeral image. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199772612.001.0001

Sobchack, Vivian. (2004) Carnal thoughts: embodiment and moving image culture. Berkeley: University of California Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1525/9780520937826

Waierstall, Alexandra. Interview with author. Virtual Interview via Zoom. October 11, 2022.

Waierstall, Alexandra. (2022) Wairstall_22_FINAL (1). [Video] Vimeo. Wairstall_22_FINAL (1).mp4 (vimeo.com)