Introduction

While I’m writing (filming), I survive.

(Lejeune, On Diary, added strikethrough and bracket by author)

Late at night, when the rustling sound tickles ears, when the dream pulls memories out to the moon, the letters start to dance on the paper with a tapping sound. One letter by letter, line by line, the surface of the paper is drenched with shadow. It is a story of someone. Someone far away from the moment but loiters over the head. Someone listens to the voice from the invisible world. Fragmented words tingle the edge of the fingertip, the prattling breaks fragile memories, and a rhythm emerges from this atmosphere.

Many diaries are written for personal reasons, documents of private life, account logs, or archives of memories with infinite possible styles. It can be for the future self or to an imaginary being as a dear diary. This form of writing does not go beyond the person who wrote or outside of the family legacy; consequently, diaries have been considered one of the most subjective forms of writing. Philippe Lejeune (2009), who was a researcher in autobiography and moved his research and practice to the diary, describes the diary as ‘like lacework, a net of tighter or looser links that contain more empty space than solid parts’ (Lejeune 2009: 153). The collected notebook then constitutes a minimal unity as an illusory narrative identity. They become a diary at the moment they form a unity as a collection. The only constraint is that it must be a subjective account of events, documenting both personal experience and objective facts.

The diary’s ambiguity and fragmentary nature have been amplified by filmmakers such as Jonas Mekas, Warren Sonbert, Andrew Noren,1 and many others who have used forms of personal recordings in their films since the ‘60s. As an aesthetic autonomy of abstract expressionism, the idea of diary film heralded a decade of parallel projects going into the seventies, footage collected on a day-to-day basis, and documentation of daily life. Its poetic rhythm, authorship, identity, and malleable materiality without a straightforward structure or style are represented in their works. In this wave of new authority, Mekas became a central figure as a film critic and experimental filmmaker who used his personal archive with uncertain movement in camera shooting and fragmentary footage editing. Particularly, his works, such as Diaries, Notes & Sketches a.k.a. Walden (1968), Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972), and 365 Day Project (2007), have been discussed in many extensions to cinema and his diaristic style. This development reveals the ongoing growth of subjectivisation in the practice of the diary in the form of moving images.

In current digital media, the practice of the diary expands its position to the art gallery and social media. It requires further questions of the fragmentation of digital materials, environmental structure, and representation of dailiness through its atmospheric expansion concerning the body of the author and the viewer. Therefore, in this paper, I examine Mekas’s methods in his performative camera shooting, collecting footage, and editing, exploring what mediates sensations using multiple frames and speculative space. Here, the diary is less an expression but a documentation that can be exposed without a temporal beginning and end, a structure without being determined by a fixed whole. The diaristic practice opens a new question on presenting undetermined relations of images, especially in the self-practice between camera, personal archive, and artist to the dynamic atmospheric space.

Jonas Mekas and Diaristic Practice

Compared to the practice in narrative film that companies with the script, the practice of the diary does not have absolute closure, clear beginning and ending. It does not end even when the author passes away, but there is a perpetual pause in its story in dreaming of immortality. In 1977, P. Adams Sitney presented the diary film as an important practice in his time, which is ‘a series of discontinuous present’ different from the autobiography; it ‘draws upon the pure lyric, and often becomes indistinguishable from it’ (Sitney 1987: 246). The notion of day-to-day practice is an exploration of the documentation of the rhythm of daily lives and as a way of living that triggers a question of how the author positions them in the current world against the habits of the mind. It allows the creation of a continuously modulating relationship between the world and the self.

As an experimental filmmaker, Jonas Mekas (1922–2019) continued his practice in diary through filmic and digital materials and the online environment, but more importantly, he was a poet before a filmmaker. At the beginning of his New York life, he pursued making a real film in the conventional sense. This plan was eventually postponed due to a shortage of funds and time, so he decided to begin shooting photographs and footage until he could make the narrative film. He transformed his practice into provisional footage, which eventually derives its own justification and telos in the form of documentation of life. Mekas reveals his thoughts in his lecture on his film Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1987) as not looking back on in memory; it is something that is measured, sorted, accepted, rejected, and reassessed based on who you are and how you are at the end of the day (Jonas 1987: 71). Privileging the position of the author in the process of shooting and editing which creates a heterogeneous assembly of sensations.

Just as the process of keeping a diary expands life with small details, the diaristic moving image demands one to awaken every moment of living through a litotes of those extremely big and small experiences. Mekas carried his Bolex everywhere and moved between the subject and the observer of his life. Keller reevaluates women’s diary literature and autobiography and finds subtle similarities that move ‘as if dancing between domestic life and artistic production’ (Keller 1992: 93). This discontinuous and nonnarrative dance of diaristic practice, Mekas describes as a series of notes. ‘I’ll film short notes, from day to day, every day’ (Mekas 1987: 190–1). For him, the practice of shooting is not a recollection of the memories but an action to the world through simultaneous filming and reflecting, emphasising the shooting should be an action of ‘without thinking or planning, just react and perform’ (Mekas 2017: 2:13–2:50). It maximises the relationship between the camera and the author. The merge between the artist’s body and the movement generated from the emotion is reflected on the camera. In other words, it documents continuously circulating between the personal life and artwork.

The shooting becomes a gesture to the outside with the performance of camera movement, close-up, and editing that omits or restructures the footage in order to deliver the feeling and sensation rather than the representation of reality. As Lejeune (2009) points out, crucial elements in the diary are the enunciation of the author on the page and the act of combining notes. The diary writers carve rhythms of continuation and discontinuation in their daily details, thoughts, shadows, and records in a limitless form that conveys reflections of life. Even in a most private and secret diary, this rhythm expresses a desire or wish to deliver or speak dailiness, whether to self, somebody, or nobody.

The digital moving image, due to its materiality, escalates the discontinuous redundancy of sound, movement, and images that are documented in separate small files, developing further allusive gaps between footage. Although most of Mekas’s practice focuses on analogue and the film camera,2 his methods offer crucial ideas on the relationship between tools and the author as a performative camera. His poetic editing illustrates the ways in which performance and editing parallel each other. With his camera, Mekas’s past memory makes the author choose which moment to shoot (Mekas and Sans 2008: 92). In another interview, he exemplifies his childhood and New York:

But I got stuck, for a very long time, with my childhood reality, so much that even my New York becomes my childhood. If you see my Diaries, you see all those seasons, winters, snow, snow, a lot of snow. What is this, how much snow does New York really have? But my New York is full of snow. How come? Because I grew up with snow. So it’s a fantasy. I am a romantic, you see, and you are … (Mekas 2020: 32)

Mekas film is structurally closer to an intuitive and automatic, building up potentials from the past and present images that come to the film and become real on the screen. Sitney argues that Mekas’s works seek to represent the entirety of the filmmaker’s life in a schematic or fragmentary performance in which ‘dates have been lost and the pages scrambled’ (Sitney 2002: 339). Therefore, what is essential in the diaristic moving image is the attitude, thoughts, and ideas of the person filming it. The moment of shooting as a latent image leads to a new relationship between reality and the artist. David E. James analyses Mekas’s two different implications and attitudes between shooting and editing, which he calls film diary and diary film. He reads double gestures of being from private events and the economy of film, creating tensions between a private and a public culture (James 1992: 147). The former challenges the hegemony forms of the medium and later entails compromises, yet also occasions new possibilities. Therefore, James argues that the diaristic practice must inscribe the figure of the author in the film or its style (James 1992: 154).

In the same vein, Lejeune argues that creating the continuation of the diary is an act of enunciation: the entry of the diary that set the date, which emerged in Western culture between the late Middle Ages and the eighteenth century following the invention of the mechanical clock and appearance of the annual calendar (Lejeune 2009: 58). The enunciation is a gesture that indicates the separation of the enunciator and their narration that ‘paves the way for the personalization of the subject matter’ (Lejeune 2009: 80).3 This gesture of enunciation derives from the understanding of self and identity, social position, the reader, and the medium it delivered. Therefore, Mekas’s diaristic practice is performatively directed to a very different point of exercises in poetry, which makes his practice neither film diary nor diary film but a continuous process of diaristic practice throughout his life.

Instead of the date number, Mekas’s films gesture enunciation in both the placing figure of the author in the image and the entry identifier describing the subject, object, or the places before each footage started. This approach shows that different methodological ideas can be applied to the properties of the author in the experimental moving image. His shooting and editing liberate the camera and form of film from the strict structure. The movement and doubling layers of reality directly connect the camera to the performance of the body. It brings the virtual past to the present, like poetry, separating and reconstructing one reality from another. Therefore, the performativity of the camera and the gestures of enunciation create intricate patterns and style in each work, which makes it seem that it is more accurate to term this as the diaristic practice instead of diary or diary film to expand the meaning of practice in the moving image.

Diaristic Experiments

As I discussed above, in both written and filmed diaries, the sensation of dailiness in the diary is neither space nor object, but in-between as a collection of experiences that are loosely connected, creating a certain repetition of rhythm compounded by feeling and thought, which are human dispositions, capacities, and needs that organise the place, space, and world. The editing of footage, like poetry, selects one particular detail from all the surrounding reality, separating and composing one experience of reality from another. The question of editing kindles another possible whole in the form of film and the space of architecture, such as how to edit the fragmented and continuously accumulating footage in one film and how to present this virtual and untimely mode of expression to the viewer without predetermined logical perception. Therefore, in this section, I examine archiving and editing in my diaristic practice through the ideas of fragmentation and multi-frame editing and expand it to the atmospheric qualities in the exhibition space in the next section.

Compared to the written diary that requires a set time each day—often in the evening—to reflect and think about the day, looking back on what happened in the period of set time, in the moving image, the camera requires immediate reaction to the situation that can take fragments of notes. The camera becomes an extension of the artist’s nerves even before it becomes an idea or thought. I have used compact and handy devices since 2019, such as GoPro, Camcorder, and iPhone, that can be attached to my body. Using handy cameras increases the chances of spontaneously acting on unexpected events and documenting shaking movements by hand and body. Therefore, I keep the camera in everyday environments in immediate situations, recording unexpected events, sounds or noise from the off-frame and collecting footage from the shortest few seconds to the longest few hours.

This action is active and reflective at the same time. Vilem Flusser defines gestures that are connected to the tool lack a satisfactory explanation for its cause (Flusser 2014: 2). He argues that states of mind are manifested in various plethora bodily movements, but they ‘express and articulate themselves through a play of gesticulations called ‘affect’ because it is the way they are represented’ (Flusser 2014: 4). The active movement depicts the sensation of the body in response to some shock, while the reactive one leads to an unconscious expression of sensation. For instance, when hot water is suddenly poured on the hand, one can react with bodily and verbal expressions of ‘hurt!’ or ‘hot!’. The active expression, however, articulates a certain movement by symbolising and codifying it by unconsciously shaking or stroking the hand.

The camera reflects the movements of the body, and the movements of the body reflect changing emotions and thoughts. These gestures of movement offer the viewer the dynamic of a space or an object as well as of a subject in imageries that document emotion and sensation. Therefore, the crucial point in editing lies in the fact that how to bring the details of movement to the surface as a documentation of daily life. These details are not what the author finds but, instead, what comes to mind, along with a potentially flowing past.

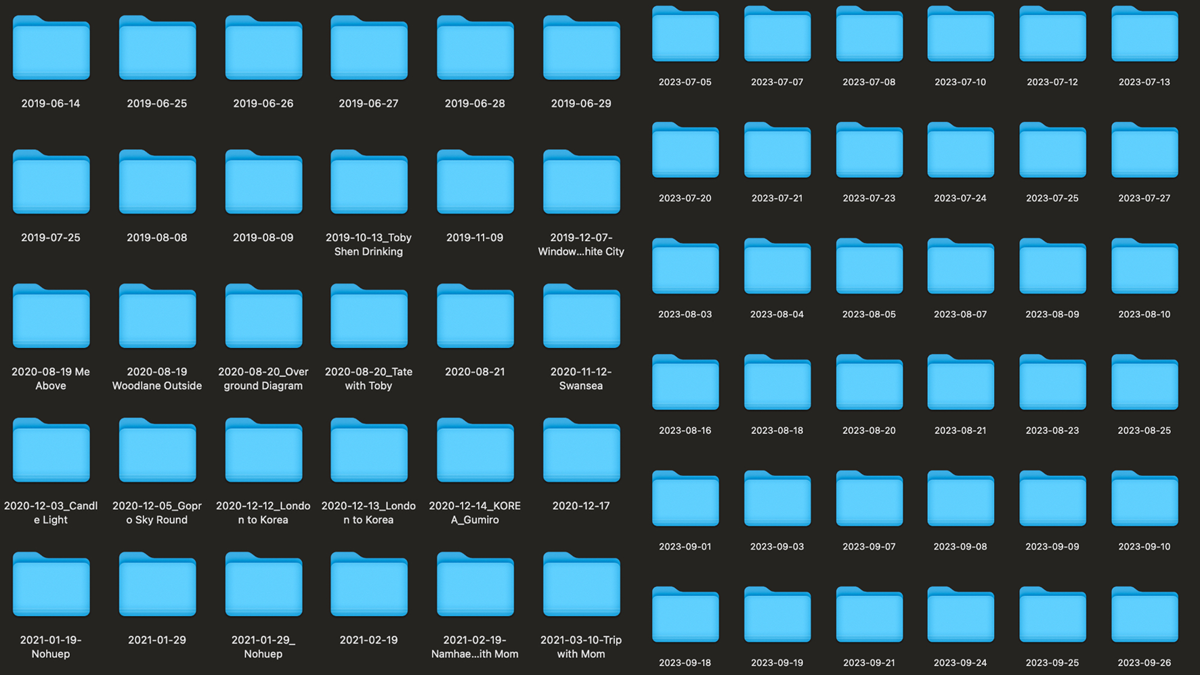

Furthermore, the method of storing the footage changes the way the artist receives the fragmentation. All my footage is digitally stored in my external hard drives in different folders using calendar-based numbers and adding keywords of place and person to identify events of videos (Figure 1). The digital archive allows me to search the footage with keywords and dates more efficiently than analogue film and dispose of losing linearity in day-to-day recording. The footage is no longer defined by the succession of time but is reorganised and reconnected with multiple images. The Square Frame experiment uses the constraint of 1 minute 20 seconds to explore the fragmentary nature and places two footages in the square ratio. The biggest challenge is the intention of selecting or eliminating the footage into nonrepresentative and abstract sensations. I aimed to challenge conventional ratio and structure, making a continuously evolving and changing movement, colour, and sound with two contradictory or parallel imageries, positioning with different sizes and positions, followed by how footage elements are interconnected. In this way, the image advocates the manner of looking at two different perspectives simultaneously.

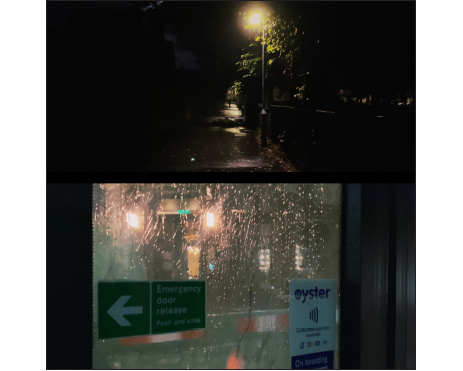

For example, in the Square Frame experiment no. 3 (Figure 2), both clips deliver a sense of going back home from different moments of back home. The top video moves inward by the camera tracking the dark pedestrian with blinking streetlights showing the contours of the surroundings. In contrast, the bottom video shows the outside of the bus through the glass, moving from left to right with shops and people passing by from outside of the bus. Both images show different movements unsettling the frame; the black bar in the middle prevents the two frames from merging into a connected one. Thereby, the viewers are not immersed in the frame space but step away and observe the tearing down of the frame space in half in contradictory movements.

In the same experiment, experiment no. 20 (Figure 3) exhibits different parallel associations based on various depictions of a rainy day. The lower image portrays a gaze peering through a window in a dimly lit room, where the contours and lines of the window and dark sky blend like pigments, obscuring the understanding of what is occurring or what lies outside. Conversely, the upper image captures a puddle with water droplets falling, sharing a similar brown spectrum as the bottom image. These two abstracted images hover in space without a connection until the sound of rain from off-frame brings them together. In this image, the sound serves as a third element that bridges the gap in the elusive experience of a peaceful rainy night.

The second version of Square Frame (Figure 4) explores the frame space expanded from the first, bringing them into a visually constructed box using the 3D computer graphics software tool Blender. It aims to open new possibilities in the moving image practice concerning the creation of a space of modulations of atmosphere in experiencing the daily surroundings. This version is intended to be displayed on the square ratio monitor instead of the projector to deliver the depth of the monitor box. Apart from two video clips, I added blinking lights and black boxes around the clip and designed light and shadow to maximise the spatial sensation. Surrounding boxes float around images, and the lights reflect toward the inner surface in different rhythms, colliding with the moving image and sound from the off-frame. It embodies sensational and aesthetic phenomena in the situation of being spatialised corporeal and symbolic multimodal modes of communication.

The editing process in my experiments plays a crucial role in capturing the details that evoke an atmosphere of dailiness, constructing a form of space, a space of feelings that can shimmer into the viewer’s body. From the shooting, archiving, editing, and formation of the box, the process gradually forms a feeling of dailiness, fragmented images looping and repeating on the monitor and the projector companied with background sound and voiceover. The tangibility of the monitor intensifies bodily interaction with the artwork and spatial expansion outside the frame. While the monitor and the light inside of the image deliver the depth of the image that affects graspable and haptic performative movement from the image, the projection delivers the pouring and filling of the space with light, creating the darkened nongravity space.

Speculative Atmospheric Space

Now, I turn to the projector display, discuss speculative space that creates an atmosphere and question how it can be offered by designing the ambulation. The moving image display requires a device or place to display the video in the space of architecture. It emerges once again in the architectural structure, which generates a new formation of spatial movement that is not determined in a single structure in the exhibition space. Through the projection in the exhibition, the moving image transmits sensations with feeling and energy of the body to the space as the painter or sculptor presses their tools against their materials. By questioning the experience and feeling of the place and space, Tuan Yi-Fu defines the experience as a person knowing and constructing a reality that covers all terms for the various modes (Tuan 2001: 8), along with the senses, experience gives us an intense sense of space and spatial qualities through kinesthesia, sight, and touch. The relationship between space and atmosphere generates multiple layers of spaces from physical, imaginary, and material.

The exhibition room shimmers in the light of projection and screen following the colour changes in the image. It dyes surfaces, faces, and bodies. The light brightens and darkens the room, expanding its movement into an empty space, billowing the emotions to the shore. The atmosphere of the architecture endows it with architectural quality, generating double layers of sensations. We receive atmosphere quickly. It is experienced even before logically and intellectually recognising what it is. The viewer’s body spontaneously responds to the atmosphere that expands from the moving image and the architecture, generating collaborative emotions back to the space. My ideas on displaying the moving image explore this notion of atmospheric experience with two speculative spaces that emerge in this spatial design: online—with social media and website—and physical space with screen and projection, questioning how to design a space of ambulation with the concept of atmosphere.

In this speculative space, the projectors are no longer on the wall or the screen but placed in diagonal and sporadic places combined with small monitor screens that can exude a particular atmosphere on the fabrics and papers, reflecting its light through materials. The gaps between screens leave spaces the viewer can walk around, and the material reflectively moves following the viewer’s movement. It is not created by the subjectivity of the artist but is more like an extension of the atmosphere of a particular form of life. Tonino Griffero and Gernot Böhme examine the concept of atmosphere in the field of aesthetics, particularly in terms of embodied experience and perception of space. Griffero analyses the atmosphere in the fields of aesthetics, phenomenology, and cultural studies and argues that it is the emotion that is poured into space as the pre-dualistic physical communication. (Griffero 2014: 108) The atmosphere is always said to be in-between mediated by the body and space, made possible by the coexistence of subject and object. (Griffero 2014: 121) The communication through the moving image fills the gap between the author’s body, image, and the viewer.

The display of projection and monitor embraces the notion of unification into relational and environmental networked collective sensations that connect both in and out of the frame. In this relationship, as Böhme points out, understanding the body and environment is the simultaneous awareness of the state of being in an environment (Böhme 2017: 18). The body is no longer a measuring reference in the three-dimensional space of reception. Following Mary Ann Doane’s analyses of the expanded cinema and the location of the image, the lights duplicate the space in dematerialisation, and the ephemeral nature of that image is reaffirmed by its continual movement and change (Doane 2009: 152). The illuminating projection guides the three-dimensional space of reception, acting as a revival of the body’s scale, reuniting the viewer and the image, allowing them to exist in a fluid, dynamic state of awareness within that space (Doane 2009: 164). The body becomes a medium of sensations that create gestures both to the camera and space, between the image and space pouring out and expanding to the physical space, affecting their very boundaries that are not limited to the physicality of the frame but also disperse to the outside, into the space, penetrating the viewer’s body.

The question is, then, how to create a multi-space between physical and online with different types of rhythm with the viewer’s own bodily and manual ambulation that directly interacts with its atmosphere instead of creating an immersive that breaks down all sensation into a dull unity of a whole. In her book Atmospheres of Projection (2022), Giuliana Bruno argues that we can observe the objecthood of screen and projection and act as if they were becoming forms of screening that have intense spatial, architectural, and atmospheric characteristics. Therefore, the atmospheric projection is not static and literal but a complex web of dynamic and influential relationships among subjects, objects, and space. These relational dynamics emerge and evolve, forming an aggregate atmosphere that is shaped by both discursive entities and the technical objects and cultural practices that constitute our everyday environment (Bruno 2022: 12, 21, 58). Above all, these projections are fundamentally characterised by the harmonious interplay between light and visual space, where the light gracefully traverses the contours of the wall or object, and its arrangement is influenced by the underlying structural forms that shape its configuration.

The encounter with the moving image can be described as a haptic and quasi-objective experience, evoking a sense of being enveloped and embraced by a distinct substance that is almost tangible, as if it has a material quality.4 This rhythm depends on whether designing a space is meant to be watched from start to finish in one sitting or presents a video that can be watched for some moment and come back later. Therefore, playing videos in a loop creates an atmospheric encounter between the image, space, and the viewer. It becomes a haptic network that enhances materiality and intimacy by the way that it affects the space, resulting in a genuine and sincere, veritable quest for a haptic space. The image moves away from the walls and corners, creating its own structure parallel with architecture by the light penetrating the viewer’s eyes, flying over their heads, around their bodies, and wrapping hands, asking them to be part of this new world.

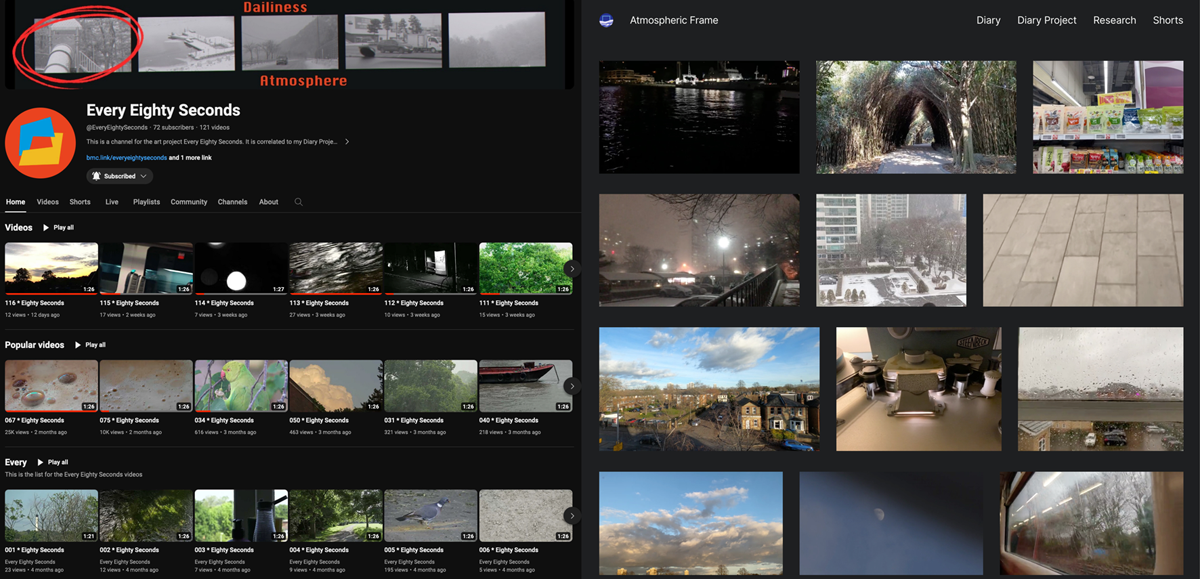

While the physical space unavoidably confronts the collision or integration of two spaces between physical and imagery, the online structure is like floating in the nongravitational void space, which suggests a rhyme of the finger. There is nobody but only hands that stroke the image’s face. On my YouTube project with the title Every Eighty Seconds (2023-ongoing) (Figure 5), my videos focus on the question of the ambulation of the finger, with the short duration and extreme close-ups that can sever the logical connection from the world with different lengths, speeds, and angles. The process of making an entry becomes uploading on social media in a uniform structure identical to its neighbours with colour, size, and design. Every time a new entry is uploaded, it triggers viewers’ devices across the space. Instead of projection lights, individual sounds and vibrations hit the sensation to allure their hand to stroke the face again as if desiring an intimate relationship with the viewer. It is different intimacy from the personal diary, as if someone glances at someone writing it, which cannot affect the viewer’s physical space but only their eyes and fingers. On the other hand, the website version, The Atmospheric Frame (2022-ongoing), explores scrolling interaction to create an individual rhythm by the user’s decision without distraction from other images unless the author intentionally puts additional empty gaps and freezes the image. This experience offers structural freedom to the author to engage with online space without design constraints into an indistinguishable structure as in other social media, such as Instagram, YouTube, and Vimeo.

Then, both online and physical spaces are displayed on the screen in the gallery space, not as reflections or supplementation of each other but as distortion and modulation into something else in a carefully calculated synchronised rhythm. The viewer encounters a distinct arrangement of frames that compose the space. In a multi-screen setup, the space hovers and shifts from one surface to another, with each screen individually presenting its image and reflecting light from various angles: front, side, and even backwards through the projector. As the viewer traverses the gallery space, the screens move alongside them, interrupting and guiding their journey away from the architectural elements, such as windows, doors, and light sources, to the imaginary map. The scattered constellation of images creates an oblique, weightless spatial experience. The architecture, projection, installation, and viewer move in the atmosphere with the image, reverberating across multiple spaces.

Conclusion

Mekas’s methods show how the form of the diary can be reconstructed through the poetic moving image. The movements of his hands and body are dancing in the camera, images are documented in this film, and finally, they expand to an atmosphere. His work shifts the enunciation of the author from the author’s body to the editing styles, and the author’s identity is once again reflected in the artwork. His work is driven by bringing his own life and dailiness to the centre of his work, making himself a collaborator of the moving image. This image of dailiness is not a given. Instead, the temporality of the diary follows its image and the practice of abstraction and absorption. The sudden realisation by wind, sound, or changes from my home or midway walking through the pedestrian, unexpected, atmospheric change that triggers the author to take a photograph or video is presented without narration and information of any kind. The moving image captured the world through the medium of the camera with its photographic precision, claiming that the world within it is the real world.

In the interview with Natasha Kurchanova (2015), Mekas answers the question about his project, the 365-Day Project (2007), what makes a complete cinema experience can be presented by all three, author, tool, and viewer together, and this intimate and personal relationship that demands new technology. My project wanders the world with my camera and expands Mekas’s diaristic practice to different stories of becoming. Within this relationship, it argues for a redefinition of the dailiness in the moving image. Moment-to-moment recordings tell a story, travelling down multiple paths without completion. My gaze wanders: I see, I move, I write, I read. I become a narrator, a listener of memory, and the protagonist being narrated. This image no longer depicts a single day of a particular person anymore. Instead, they are montage spaces as a way of showing the various modulations of the atmosphere.

Again, a question returns to the surface of how this speculation can be presented and designed to connect, disconnect, and expand to the atmospheric space. The world is not empty or sensitised space but filled with atmosphere, light, sound, movement, and the vibrations of emotions in the between space. In this exhibition space design, the images refuse to be absorbed into the architectural structure and diligently embody their own becoming. It is a quasi-space that blossoms as soon as the audience enters and disappears when they leave and the lights go out. The image and architectural space should not be a reflection of the mirror but parallel spaces facing each other. This space witnesses the relationship between the camera and the hand that is closer than the eye. Through direct contact, the hand becomes the camera, and the camera becomes the hand. This sensory documentation is once again expanded within the exhibition space, becoming a collaborative space with the audience.

This becoming is the story I want to tell in my diaristic practice.

Notes

- Warren Sonbert and Andrew Noren are American experimental filmmakers who actively engage with their actual life recordings in their work. Sonbert’s films, Where Did Our Love Go? (1966) and In Search of the Miraculous (1967) pays close attention to details of his surroundings, people, and individuality. Noren’s The Adventures of the Exquisite Corpse film series from 1968 to 2008 has an autobiographical and testimonial dimension, examining the abstraction spaces and times. [^]

- In 2007, Mekas experimented with the digital and online environment in The 365-Day Project (2007). He recorded videos every day and uploaded them on his website, which evidences that his practice is not searching for essence film material but in the performance of tools and the author. [^]

- While this text mainly discusses diaries as a historical and aesthetic practice in Western culture, there are possible forms in East Asian countries, such as diary literature and Haiku, that can exemplify other expressive forms of diary practice. Roland Barthes discusses how Haiku expresses experiences of betweenness together with the seasons and movement and indirectly shows the author behind the scenes (Barthes 2005). [^]

- Finnish architect and educator Juhani Pallasmaa (2014) explores atmospheric nature in the experience of architecture. For more information, see Juhani Pallasmaa (2014). [^]

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Author Information

Il Sun Moon is a PhD candidate in film and photography at Kingston University London. Throughout her academic experience in communication design in China, Japan, and the UK, she gradually became attracted to diagrammatic practice in moving image practice. Her recent work focuses on the diaristic practice and its spatiality in atmospheric expansion. Thus, it challenges the conventional structure of time and cinematic spatial qualities in the form of experimental practice and aims to deliver the importance of producing a synthesising body of work between research, moving image practice, and personal experience.

References

Barthes, Roland 2005 The Neutral: Lecture Course at the Collège De France (1977–1978). Translated by Rosalind E. Krauss and Denis Hollier. New York: Columbia University Press (European perspectives).

Böhme, Gernot 2017 The Aesthetics of Atmospheres, ed. Jean-Paul Thibaud. London: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315538181

Bruno, Giuliana 2022 Atmospheres of Projection: Environmentality in Art and Screen Media. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Doane, Mary Ann 2009 ‘The Location of the Image: Cinematic Projection and Scale in Modernity’, in Art of Projection ed. Stan Douglas, Christopher Eamon, Beatriz Colomina, Branden W. Joseph, and Mieke Bal (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz) 151–165.

Flusser, Vilém 2014 Gestures. Translated by Nancy Ann Roth. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816691272.001.0001

Griffero, Tonino 2014 Atmospheres: Aesthetics of Emotional Spaces. London: Ashgate Publishing.

James, David E. 1992 ‘Film Diary/Diary Film: Practice and Product in Walden’, in To Free the Cinema: Jonas Mekas & the New York Underground, ed. David E. James (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press) 145–179. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780691219554-011

Keller, Marjorie 1992 ‘The Apron Strings of Jonas Mekas’, in To Free the Cinema: Jonas Mekas & the New York Underground, ed. David E. James (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press) 83–96. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9780691219554-006

Kurchanova, Natasha 2015 ‘Jonas Mekas: “I Have a Need to Film Small, Almost Invisible Daily Moments”’, Studio International. Available at https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/jonas-mekas-interview-365-day-project-microscope-gallery-brooklyn [Last accessed 28 October 2023].

Lejeune, Philippe 2009 On Diary, ed. Jeremy D. Popkin and Julie Rak. Translated by Katherine Durnin. Honolulu: Published for the Biographical Research Center by the University of Hawai’i Press (Biography monographs).

Mekas, Jonas 1972 Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania. The Film-Makers’ Cooperative.

Mekas, Jonas 1987 ‘The Diary Film’, in The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, ed. P. Adams Sitney (New York, N.Y: Anthology Films Archives) 190–198.

Mekas, Jonas 2007 365 Day Project. Available at http://jonasmekasfilms.com/365/month.php?month=1 [Last accessed 28 October 2023].

Mekas, Jonas 2017 ‘Jonas Mekas – Always Beginning’. YouTube: TateShots. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kzkzQExJ9rc [Last accessed 28 October 2023].

Mekas, Jonas 2020 Jonas Mekas: Interviews, ed. Gregory R. Smulewicz-Zucker. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi (Conversations with filmmakers series). DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/jj.399533

Mekas, Jonas and Jerome Sans 2008 ‘Jonas Mekas: Interview with Jerome Sans,’ in The Everyday, ed. Sans Johnstone (London: MIT Press) 92.

Moon, Il Sun 2022 Diary Film Project, Atmospheric Frame. Available at https://atmosphericframe.com/?page_id=25 [Last accessed 28 October 2023].

Moon, Il Sun 2023 Every Eighty Seconds. Available at https://www.youtube.com/@EveryEightySeconds [Last accessed 28 October 2023].

Noren, Andrew 1968–2008 The Adventures of the Exquisite Corpse (Film Series).

Pallasmaa, Juhani 2014 ‘Space, Place, and Atmosphere: Peripheral Perception in Existential Experience,’ in Architectural Atmospheres: On the Experience and Politics of Architecture, ed. Christian Borch (Basel: Birkhäuser) 19–39. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9783038211785.18

Sitney, P. Adams 1987 ‘Autobiography in Avant-Garde Film’, in The Avant-Garde Film: A Reader of Theory and Criticism, ed. P. Adams Sitney. New York, N.Y: Anthology Films Archives (Anthology Film Archive series, 3) 199–246.

Sitney, P. Adams 2002 Visionary Film: The American Avant-Garde, 1943–2000. Third edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sonbert, Warren 1966 Where Did Our Love Go?.

Sonbert, Warren 1967 In Search of the Miraculous.

Tuan, Yi-Fu 2001 Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Eighth Printing. Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press.