Introduction

What happens when the circus comes to visit? A frame for the performance must be fabricated or repurposed: a tent, a hall or an arena, at the very least a ring (Greaves 1980). Some sports ground or civic structure, field or street corner must be re-territorialised before the bodies of the acrobats and the clowns are put through their paces. A circle drawn; the earth smoothed. These architectural gestures liberate the performers and make possible the substance of the performance, the matter of the circus: the acts and the tricks and comic vignettes that provide a temporary shelter for the composition of extreme sensations (Tait 2005). But how is this ring defined? And once the circus moves on, relocating to its next site, its next performance, what trace of the ring remains – for audiences, for the company? How might a digital record or database history make meaning of the travelling circus, of the processes of motion and stasis that connects a touring performing arts company with the spaces and places it occupies and the processes of exchange it embodies?

This paper analyses the multiform traces of tour activity – preserved in digital archives and digitisation projects – by Australia’s longest-running contemporary circus company – Circus Oz. Arising from a digital circus data project, called Radical Exchanges, we seek to develop new methodologies for understanding the personal, political, technical and aesthetic exchanges that give shape and texture to the past and present of a contemporary circus company.1 For these purposes, Circus Oz provides a unique opportunity: a contemporary circus company with a touring ensemble that has produced an abundance of data across more than four decades of operation, much of which is born digital or has been digitised.

Known internationally as an ‘icon of the New Circus movement’ (Bouissac 2012: 194), Circus Oz emerged from an active performing and visual arts scene centred around the Pram Factory in Melbourne, Australia, in the 1970s. From its inception in 1978, Circus Oz was vocal in its support of indigenous land rights and nuclear disarmament, it was pro-feminist, anti-racist, and collectivist in its operations. The company has also advocated for the rights of asylum seekers in Australia. The company’s activism, directly informed by its agitprop roots, relied on parody to call out social mores and political issues, while simultaneously ‘lampooning and affirming the link with ‘traditional’ circus’ (Baston, 2015: 218). Circus Oz performances, incorporating the collectivist ideals of a collaborative assemblage, were built on the premise of individually developed acts stitched together to create at times chaotic, energetic, hilarious and changeable shows that nevertheless toured extensively, both within Australia and around the world.

Circus Oz has maintained a wealth of information about its show history, training and technical practices, personnel and wider community engagements. Most notable is their extensive video archive, which includes documentation of hundreds of performances and rehearsals. As Jane Mullet (2015: 201) observed in her reflection on the Circus Oz Living Archive (COLA), ‘Circus Oz began in the decade in which video technology became commercially available.’ This fact proved significant in that from the outset Circus Oz documented itself. Across a variety of video formats and with variations in quality, the circus captured the remnants of its performances: bodies in motion and the mobility of its touring. These videos, now themselves digitised data thanks to the COLA project, complement the still photography, company records, printed programs, scrapbooks of news clippings and other ephemera that are the material traces of the touring circus.

In this respect, COLA reflects what Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin in their 1999 book on Remediation: Understanding New Media have argued is the distinction between immediacy and hypermediacy in the interaction with web technologies.

Where immediacy suggests a unified visual space, contemporary hypermediacy offers a heterogeneous space, in which representation is conceived of not as a window on to the world, but rather as ‘windowed’ itself—with windows that open on to other representations or other media. The logic of hypermediacy multiplies the signs of mediation and in this way tries to reproduce the rich sensorium of human experience. (1999: 33–34)

The event of the circus which was contained by the immediacy of the live event, and its role in living memory, is thus multiplied and remediated through the hypermediacy of the windows that are opened by the archive. These windows make possible the traversal of a multiplicity of spaces that construct the mobility and history of Circus Oz. Looking in particular to a set of tours to remote indigenous communities in the Northern Territory between 1985 and 1993, this article introduces a data-assisted examination of circus touring as a site of performative encounter and spatial negotiation.

Giving shape to this project is the notion of the ring, or rather the potential for a multiplicity of rings (literal, performative, heuristic). The circus semiotician Michael Boussiac when writing about the uses of the ring describes the ways in which the acrobatic tricks follow a narrative and rhetorical pattern that involves sudden changes in appearance and disappearance, as well as in mood or evocation. When the magic of the ring concludes:

a kind of puzzlement lingers in the mind of the audience. A few tricks were quite obvious and only required perfect skills and clever props. The fast pace of the actions did not leave much time for observation and reflection. But how could the two girls who were locked in the cage suddenly come back from outside the ring? There remains in many spectators an after-taste of uncanny wonder. (2012: 49)

While accounting for a very different aspect of the fascination of the circus in this account, we seek to rethink the potentialities of the ring as a form of uncanny wonder in which what appears and disappears is modified by the skills, technologies and interactions of digital archive and data analysis. In the sections that follow, this article enters the rings that define the spaces of scholarly enquiry, the data model, and the digitised performance record, to interrogate how meaning and knowledge are shaped by the frames applied to them, and how the shifting perspective offered by computational research might offer a lens through which these rings might be rethought.

Conceptual Rings: Thinking Through Movement as Data

In introducing their interest in tracing ‘dynamic spatial histories of movement,’ Harmony Bench and Kate Elswit (2016) argue for the confluence of digital and traditional research methods. The scalability of digital data enables a different perspective, the capacity to reimagine global space and power dynamics that sharpens attention of where focus on specific questions might be directed (2016: 589-591). Meanwhile, it is the photograph, the diary entry, the traces left by individual performances that provides clarity on the particulars of past performances and the quotidian processes of movement on tour. Through this process of zooming out and zooming in, as it were, the specificities of ‘movement on the move’ becomes discernible, and through that the ‘complexity of touring as an object of study’ comes into focus (2016: 577, 575).

This recognition of movement as data, and indeed the potential of data as movement or even performance, that flows from Bench and Elswit’s work is significant in framing this project. A conceptual ring forms through the affordances offered by thinking about the performing arts as generators of and sites for data analysis. If, as Miguel Escobar Varela (2021: 141) observes, theatre, and the performing arts more broadly, represent rich sources of spatiotemporal data due to their being ‘bound in time and space more than many other artforms’, then the mobility encountered through the touring company adds even more layers. As Bench and Elswit observe, ‘There is a huge potential for analyses of touring to help us understand larger ecosystems of performance, past and present’ (2016: 576). In the case of Circus Oz, looking to the data that adheres to their extensive touring history provides insights not only into the shape of national and transnational performing arts networks, but also enables an exploration of the company’s evolving performance ethos and style.

Giving shape to this data – both in terms of its generation and interrogation –are a number of important scholarly gestures and strokes that sketch the conceptual rings of this project. The first rests on the significance of travel, mobility and movement in understanding the evolution of a touring performing arts company. If the mobility of a circus company generates data, it also creates enduring narratives. In the case of Circus Oz, this has most often been shaped as a narrative of transnational encounter, in which skills and style are both performed and shaped through their exposure to different international cultural traditions (Mullet 2015: 207-209). A focus on the international mobility of Circus Oz reflects the predilection observed in relation to dance by Bench and Elswit of ‘accounts of transnational contact that privilege certain large metropolitan areas’ (2016: 578). Yet, the narrative of outward travel is only part of the picture revealed by looking at the spatiotemporal data of Circus Oz. As is explored below, there is another set of intranational encounters that reveal a different perspective on the company’s performance history.

An exploration of such inward mobility of a nationally touring company presents the opportunity to examine a different perspective. In this case the process of touring as a genre of movement plays against historical and colonial antecedents. In zooming out to the level of abstraction, where ‘tours are represented as point-to-point lines’ (Varela 2021: 148), the 1988 Circus Oz Arnhem Land tours seemingly retrace the movements of the historic, if anachronistic, 1948 American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land (Thomas 2011). Undertaken as a scientific survey, the 1948 Expedition was already, as Martin Thomas (2011: 2) argues, an outmoded undertaking, combining the practice of nineteenth century exploration with an emerging cold war performance of trans-Pacific relationships. The resulting exercise in mobility worked to emphasise the western settler project of the expedition as genre of movement (Thomas 2011: 18), one which works to both showcase and exert the presence of the western traveller over the examined space. In many ways, the touring impulse of Circus Oz, as a white settler performing arts company heading once more into Arnhem Land some 40 years later, replicates this earlier moment of exploration. Yet on zooming back in on the specificity of performance additional context is revealed. The parody and politics that underly Circus Oz performances, as is explored further below, subvert this earlier mode. Yet the frame of movement as genre and movement as data remain important lenses through which to view and interrogate such mobility.

This interest in mapping movement signals then the next of our framing gestures. This project is an extension of the conceptual space that has emerged at the intersection of performance studies, theatre studies and the digital humanities. If questions of how data analysis might assist understandings of movement and mobility give one point of reference, then another lies in the activation of methods for mapping spatiotemporal data (Varela 2021) and defining the data model (Bollen 2016). In this respect, Radical Exchanges owes much to Varela’s articulation, by way of Bodenhamer, of deep mapping as a means for interweaving topographical data with ‘critical commentary to enable the narrativization and contextualization of spatial data’ (2021: 147). This mode of data-assisted exploration enables a questioning of not only what is made possible by considering circus as data, but what multi-layered meanings of place and encounter become possible when interrogating such data at multiple scales of distance and closeness, and from a variety of perspectives.

Completing, if not closing, these conceptual rings are the potentialities of transference that sit within these previous framings. Drawing on the work of John Urry, Bench and Elswit observe:

Underlying mobilities in themselves […] do nothing; it is necessary to account for the social consequences of such mobilities. To think about touring in this way is not only to tell the story of a star performer and her most famous audience members, but to consider the ripple effects and residual affects of many travelers’ arrivals, departures, stays, and returns. (2016: 581)

Alongside questions of what and how movement took shape through a touring arts company, there are important questions to consider in terms of the impact such movement had. For Bench and Elswit, touring produces observable exchanges between audiences and artists, in terms of the memories made and the new dance styles learned (2016: 583). This notion of artistic and performative exchange is also elucidated by Bollen (2016: 627), who explains in relation to the affordances of the data model, ‘[b]y following the trajectories of people, companies, productions, and works through time, across space, and among performances, we begin to see the dynamics of transmission.’ This process of transmission, which accounts not only for the traces left by the touring company but also the influence and incremental change reflected in the company, provides the evidence of touring as a process of friction as well as movement.

What is sketched here is the first layer of rings that occupy this project. The research environment, which structures or contours the possibilities of this research, also delimits the place (lieux) of this project. Specifically, this project moves from the conceptual into virtual space, where the researchers attain mobility and can explore. In the next section, we enter the virtual ring to explore the circuit of overlapping, evolving imminences, in digital platforms that mediate the data model of this project.

Entering the Virtual Rings: AusStage, TDP, CIRCUIT, TROVE

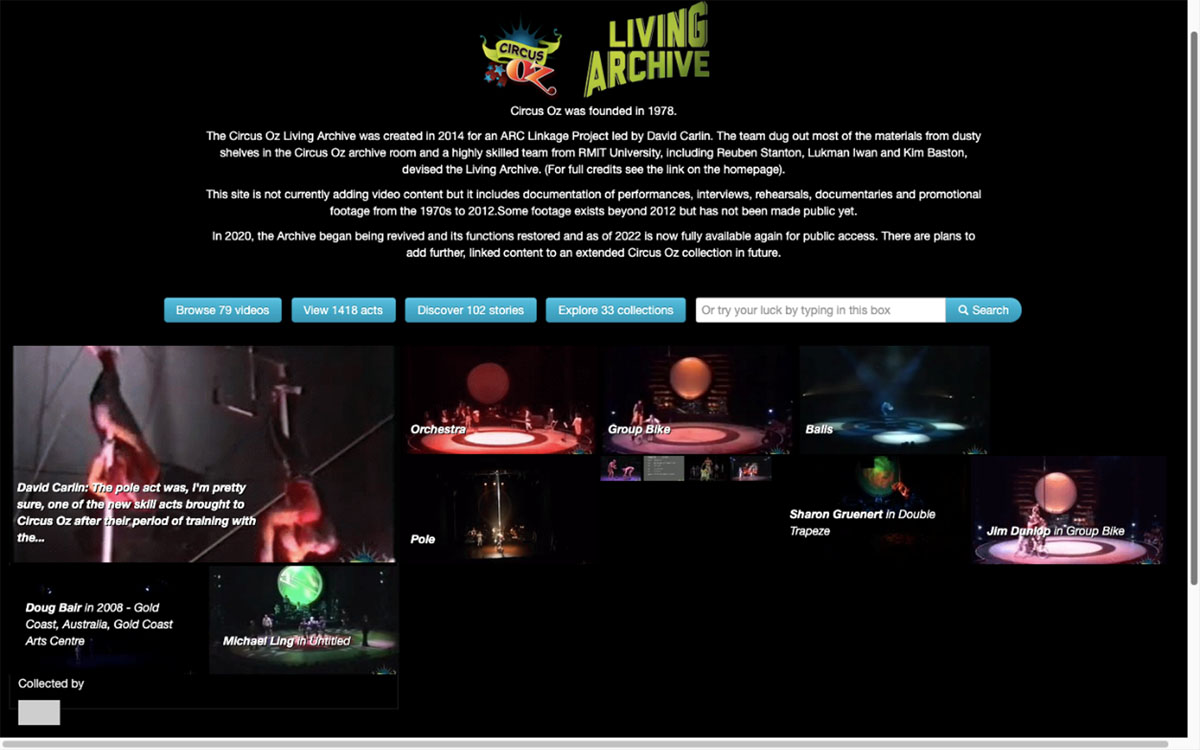

To encounter the Circus Oz Living Archive (COLA) is to address a screen of whirring rectangles (Figure 1), each frame a container for a mini-performance: a body flicking or turning, dressed as a dog, riding a bicycle or shooting fire. As David Carlin, a former artistic director of Circus Oz and one of the architects of the site notes, COLA extends

the logic of the live performing arts, which is all about the ephemeral live experience, not into a state of stable permanent storage – the cryogenic archive – but into an enduring, evolving digital event. (Carlin 2015: 36)

The digital archive thus becomes a space in which the circus can perform the organisation and reorganisation of its virtual artefacts – its videos and other ephemera – setting them in motion in a shifting play of relational logics that is itself a performance. The unique design of this digital platform, which the project research team calls its liveness, seduces the viewer into a state of wonderment, so that the archive replicates the affective achievement of the circus for users of the online site (Vaughan 2015: 75).

As Bouissac recounts

Research on contemporary circus indeed starts online. The websites put up by individual artists, troupes, agencies, and companies provide a wealth of information not only on the organization of the trade but also on the contents of the spectacles they advertise. Virtual data, both visual and verbal, and the musical background that comes with the video clips are relevant to the inquiry of the ethnographer who endeavors to explore the interface between the circus and its audience. (Bouissac 2012: 10)

By curating an online website that could support the digital video documentation of nearly forty years of touring live circus performance, the company, in consultation with information architects, were alive to the potential within the curation and collection of historical materials in a digital environment to continue transforming social and creative relations. Digital archives that emphasise interactivity and user participation create opportunities for the incorporation of multiple perspectives and voices, as well as presenting complex and multi-layered materials in a way that is engaging and potentially meaningful to users. The development of this website was guided by the concept of an organic or living archive where cultural materials are not treated as fixed and unchanging, but as constantly reshaped and reinterpreted by different individuals and communities. By allowing for ongoing user participation and engagement, a living archive can capture and reflect ongoing changes and transformations. It is a concept which has had a significant currency in the field of archival studies and projects; indeed, the liveness of user interactions with the archive, facilitated by the intrinsic dynamism of the digital medium, are often interposed in relation to the ‘deadness’ of the archive as institution and authority (Burdick, Drucker & Lunenfeld 2012: 47).

The beginnings of COLA can also be traced to an imperative need to gather and record the history of the company, particularly as company members were aging and their own collections of artefacts were widely dispersed and, in some cases, also forgotten. As a recuperative project, the Living Archive thus focussed on ensuring that aging VHS, Betamax, Mini DV and U-matic tapes, that could potentially become unreadable as they reach the age of digital obsolescence were digitised in high resolution formats, provided with relevant metadata, and preservation copies stored in a permanent archival repository. The company members, which notably also had ‘collective ownership’ over their work, their history and the organisation, wanted however something more than a preservation strategy, they also sought a means to tell personal stories that could account for the vernacular and anecdotal aspects of transmitting expert knowledges about their collective history.

The windowed interface of COLA therefore includes digitised video divided into acts such as trapeze, acrobatics, clowning tricks (that are the units of meaning created and ‘owned’ by individual performers) within a show. The accumulation of personal contributions to the archive in a continuous circle of meaning-making around the visual content becomes thus a digital artefact of collective storytelling, a remediating of digitised moving image content that allows another ring of interpersonal meaning to emerge. It is also however, nearly a decade after its creation, a product of the histories of technology that created it, tied through the grid to a proprietary video streaming platform, and to a certain evolution of the digital archive and its technical and methodological affordances. As a digital memory of Circus Oz, COLA also performs as a version of the circus: an internally constitutive set of relations presented in a tabular format. The ‘grid’ structure of the website records and represents the singular performance as well as the informal interactions, but also separates those relations from the space or place of its performance, much as the seating arrangements in any ring or demarcated performance space will do.

The delirious pleasures of the COLA website are also its frailty: it is expensive to maintain and complex to repair when broken. This frailty, in a sense, is an accepted feature of the COLA project. In Performing Digital, a book-length study of the Living Archive, David Carlin acknowledged the difficulty that the company would face in nurturing and sustaining the archive after the academic research team handed it over: ‘[It will be] a challenge indeed when the survival of any arts company is itself a feat pushing against the forces of entropy and decline.’ As such, after more than a decade and at a time of straitened finances, during the first months of the COVID pandemic when all performances were stalled, the company asked software engineers at the University of Melbourne to rescue the site, by funding the transfer of files to a new storage system and rebuilding links that had been lost. This relocation of the server also provided an opportunity for digital archivists and performance researchers to look ‘under the bonnet’, to peer into the structure of the system that had created this ‘living’ manifestation of the circus and its legacy, and ask again what constitutes a ring? What form might another ring of archival performances take? And who belongs in the ring? In particular, what lingers in the digital ring of its diverse audiences as an ‘after-taste of uncanny wonder?’

‘Data-assisted’ research was already underway with the Theatre and Dance Platform (TDP), a digital repository hosted by the University’s Baillieu Library and using the open-source DSpace software package for library systems to house scholarly and published digital content (Varela 2021: 8). With its internal cataloguing structure, and in consultation between technicians and researchers, this software has been adapted to a greater range of digital materials – films, photographs, drawings and audio-files – from contemporary Australian theatre and dance companies. By adding the relevant metadata to record the correct venue locations, names of artists, dates and other explanatory content, the TDP can ingest existing digital materials making them readily available in searchable, and downloadable formats (that incorporate appropriate copyright acknowledgements for each resource). On one level, the repository flattens out the materials – they do not appear simultaneously except in the standard faceted search function of lists and icons, and through the active deployment of key search terms.2 It does not however determine the mode of viewing of a trick, or the focus on a particular artist but releases the researcher to locate works by media, date, person, or location, and to compile a list of items with any search.

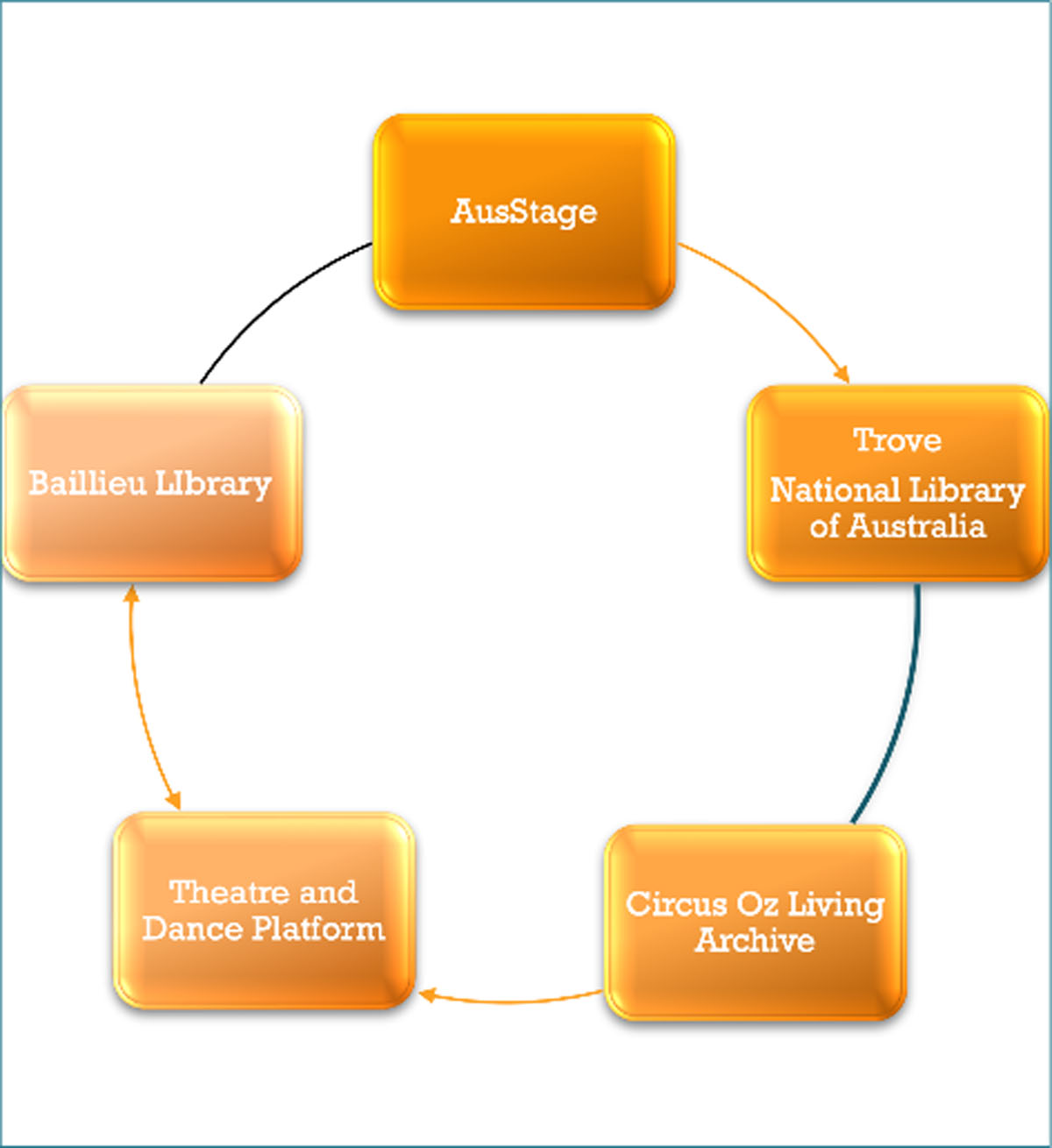

The TDP is not however an isolated end point for these resources; on the contrary, each digital object becomes available to circulate in ever wider circles through an open API that shares metadata across and between collections. As a result, the Circus Oz metadata becomes linked to AusStage, the national performing arts database, and a digital object in the University DSpace repository can be located via an open query search on circus either in AusStage, or through the National Library’s search engine, Trove, through a harvesting agreement with universities and other content providers. The interoperability (Figure 2) of this metadata increases access to the original resources associated with any individual event in the digitised rings of Circus Oz history; no longer associated directly with the ‘living archive’ of the circus community itself. The DSpace repository of TDP with its faceted searching interface allows for other combinations of resources to be identified across and within events, or in relation to specific media, or of an individual artist, rather than be shaped by trick or personal story. On one level, the atmosphere of unruly chaos is disaggregated in favour of a relational methodology determined by the user or researcher, hence allowing Circus Oz to become distributed, if less recognisable to its artists, within the information architectures of national collections and other aggregative systems (see Bollen 2016).

Datafication of the digital objects releases the use of other digital tools for analysis of Circus Oz’s history; one of which is a mapping interface called CIRCUIT.3 Funded by an Australian Research Council project, Creative Convergence, CIRCUIT intended to examine the impact of touring and regional theatre for young people. In partnership with software engineers in the Melbourne Data Analytics Platform, this mapping tool represents a relational network of theatre activity showing specific features drawn from AusStage such as company, titles, venues, genre and date ranges on a map of Australia, as well as providing layered interfaces on educational, social and economic distribution that draw upon Australian Bureau of Statistics data. Designed for interaction by and with theatre companies, we recognise that while such data can be situated on a map, interpretation of that data in local networks of theatre production and meaning is also critical. As Gabriel Hawkins suggests, ‘digital maps should always be seen as provisional, problematic, contaminated: [but] they are useful to think with and against, but not to ground our histories on’. With CIRCUIT, AusStage, and the Theatre and Dance Platform rupturing the space of COLA’s grid, we were able to examine three distinctive features in CIRCUIT that relate to mobility:

patterns of spread of activity across centres and peripheries;

scale and concentrations of activity over time;

and degrees of access determined as likely opportunity to see a theatre show.

Spatialising the touring networks and identifying points of convergence or gaps in theatre as localised events would, we hope, provide some new insights into larger performance ecosystems that shape access to theatre, and perhaps in turn shape what happens in the ring.

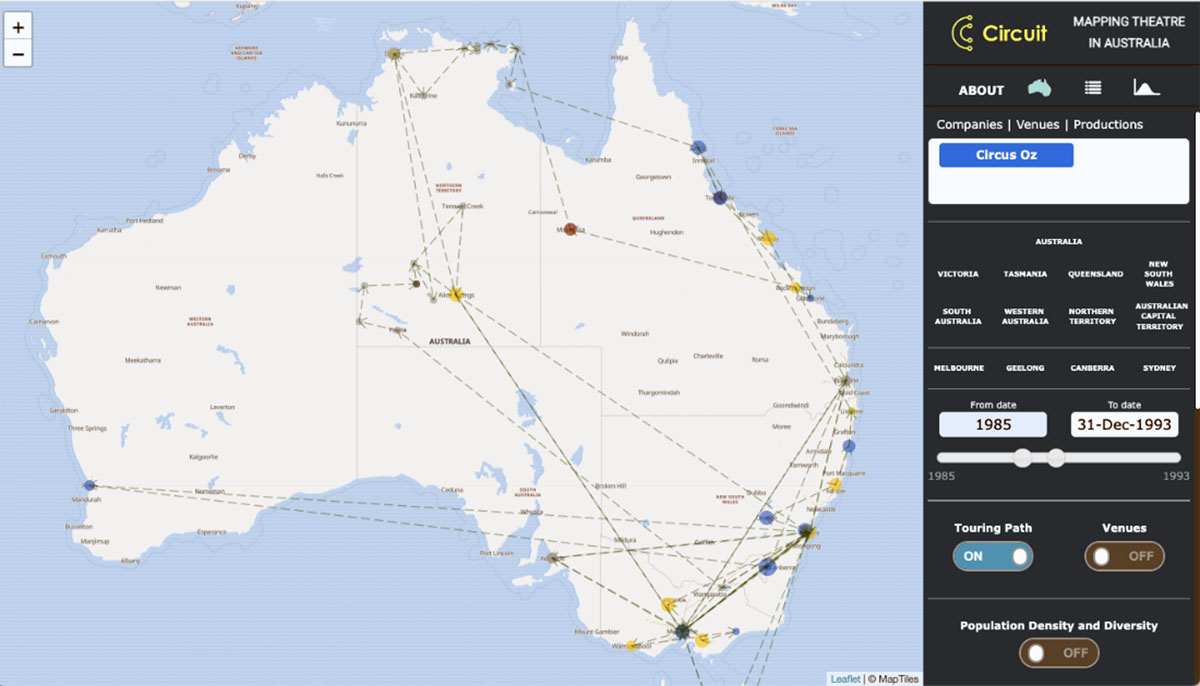

In terms of Circus Oz, the time-mapping of their touring schedules in CIRCUIT reveals a dense web of activity around the nation, back and forth across flightpaths between capital cities on the coastal periphery, with regular divergence along regional cities and towns. Three touring circuits in the years between 1985 and 1993 were anomalous to these repeated lines and pathways, and they formed a ring shape through the middle of Australia and around the ‘top end’. In terms of scale of production, these events were minoritarian – in the sense that these were not events in the service of majoritarian powers – when compared with the extensive durational touring undertaken by the company throughout the 1990s that extends to a global mapping of their influence. However, these rings located in small-scale indigenous communities required further investigation because they involved repeat visits over long distances and were beyond the standardised circuits of theatrical production and circus touring.

As the map (Figure 3) shows, in July and August of 1985, the company travelled through the vast Alice Springs region of Central Australia, its first tour since returning from the Los Angeles Olympic Arts Festival in 1984. It began with six performances at the Araluen Arts Centre in Alice Springs. The company then performed at the Yuendumu Sports Carnival, a long-running festival that attracts thousands of Indigenous participants and spectators from across the Northern Territory and beyond. The next stop was the school in the outback settlement of Papunya. The company then went to Kintore and Docker River, before finishing with two performances at Uluru, including a sunset performance for what was then called the Ayers Rock Community but is now known as the Mutitjulu Community.

In June and July of 1988, the company toured in North and Far North Queensland. After travelling to Normanton, a port and outback town on the Norman River, the company flew on a chartered Douglas DC-3 propeller-driven aeroplane run by Air North to Arnhem Land. After landing at the Groote Eylandt Airport, the company of nineteen performers and crew lodged at a local mining camp, and the next afternoon, on Saturday, the company performed for the Angurugu community. Their next stop was the Yolngu community of Yirrkala, in the East Arnhem Region on the Grove Peninsula. After Yirrkala, the third stop on the 1988 tour was Galiwin’ku on Elcho Island. From there, the company flew back to the mainland, to Ramingining, before their final Arnhem Land stop at Maningrida. The tour concluded with shows in Katherine and Darwin.

In 1993, the company returned to settlements they had previously visited as well as some new venues across Central Australia and Arnhem Land. Beginning in Alice Springs on 15 September 1993, the DASET Tour went to Tennant Creek, Yuendumu and Hermannsburg in Central Australia. There was then a short season in the Performing Arts Centre in Darwin before the DC-3, nicknamed the Silver Surfer, took them back to Arnhem Land. On this tour they went to Maningrida, the islands of Milingimbi and Galiwin’ku and, finally, Yirrkala.

Rings within rings, circles within circuits: the localised audiences assemble and re-assemble, so too the research process in which the materials of the circus in digital form – videos, photographs, posters, stories and data – can be placed alongside other digital artefacts pulled from the interoperable networks of digital resources in other collections and places, such as the National Library’s newspaper collection which releases images of central desert communities, articles from newspapers and magazines, as well as the necessary recognition of indigenous bodies and voices in the living encounter with Circus Oz. There is also an intensification of the specific formal properties that activate the circulation of digital objects, the trails they make and the narratives they produce – these new relations between the physical livedness of the event, and these epistemological copies are not uncomplicated: they digress and recede as they provide new opportunities and dilemmas for understanding this circus at that time, in those places. And they do so in ways that are ring-like, but ‘more than circular’, as Celia Lury argues for the ‘epistemological values [that] are constituted in circulation’ by digital platforms (2021: 168).

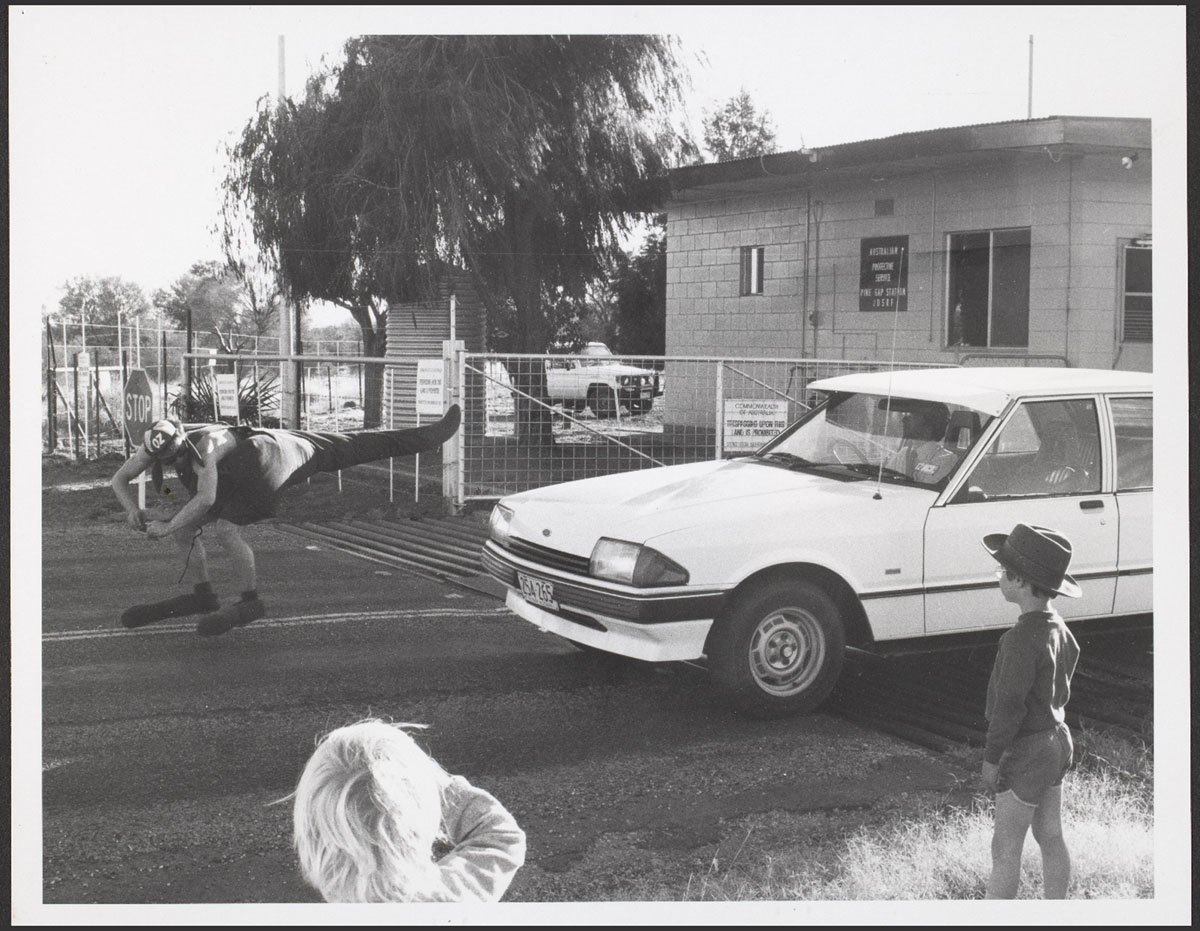

Material Journeys and Virtual Journeys: Reconstructing Circus Oz Tours 1985-93

As Bollen writes, it is the ‘rich descriptions and interpretations, not the abstractions of data models’ that ‘preserve the artistic, linguistic, and cultural authenticity of performance and archival sources’ (2016: 621). Navigating the intersecting rings of the distributed Oz Circus archive, traces of these tours through Central Australia and Arnhem Land are brought momentarily into the spotlight, suggesting new lines of inquiry, new perspectives and understandings, and possible narrative beginnings. We find, for example, traces of the company’s activist tendencies, focussed and given form by the tour itinerary. Following the shows in Alice Springs, the company staged a colourful protest event at the military Pine Gap satellite surveillance facility on Tuesday 20 July 1985. The event is documented in the company’s own 1985-86 show programme, which reproduces an article from the Centralian Advocate. A performer costumed as one of the iconic Circus Oz red kangaroos confronts Australian Protective Services officers guarding a facility gate (Figure 4). This episode was part of a series of protests at the military Pine Gap satellite surveillance facility – such as the November 1983 Pine Gap Women’s Peace Camp – and is a reminder that Circus Oz was formed in the anti-militarist milieu of left-wing political theatre in Melbourne in the late 1970s. The Pine Gap protest is also a reminder of the many ways in which the stresses of the Cold War shaped the colonial project in the Northern Territory and throughout remote and regional Australia.

Following the Pine Gap protest, and travelling in a convoy of four cars, the company toured through five communities west of Alice Springs in the Tanami desert belonging to the Warlpiri people. At Papunya, a local account of the performance was written by students for Warumpinya ngurrara kuulaku piipa, the school newsletter, and printed in both English and Pintupi-Luritja language, the school having committed itself to teaching a bilingual programme in 1984. A digital copy of the newsletter can be found in Trove. Their report and the accompanying illustrations inverts – albeit not unproblematically – the knowledge paradigm in which Indigenous peoples are represented in archives as the object of the gaze of governmental agents (Russell 2005: 161). It describes a show with an open workshop structure, in which students were encouraged to play with the musical instruments and circus equipment. Some of the pictures of the performance drawn by the students represent the audience using groups of U-figures, a device used in the work of many Papunya Tula and Western Desert artists to indicate a meeting place for Indigenous peoples.

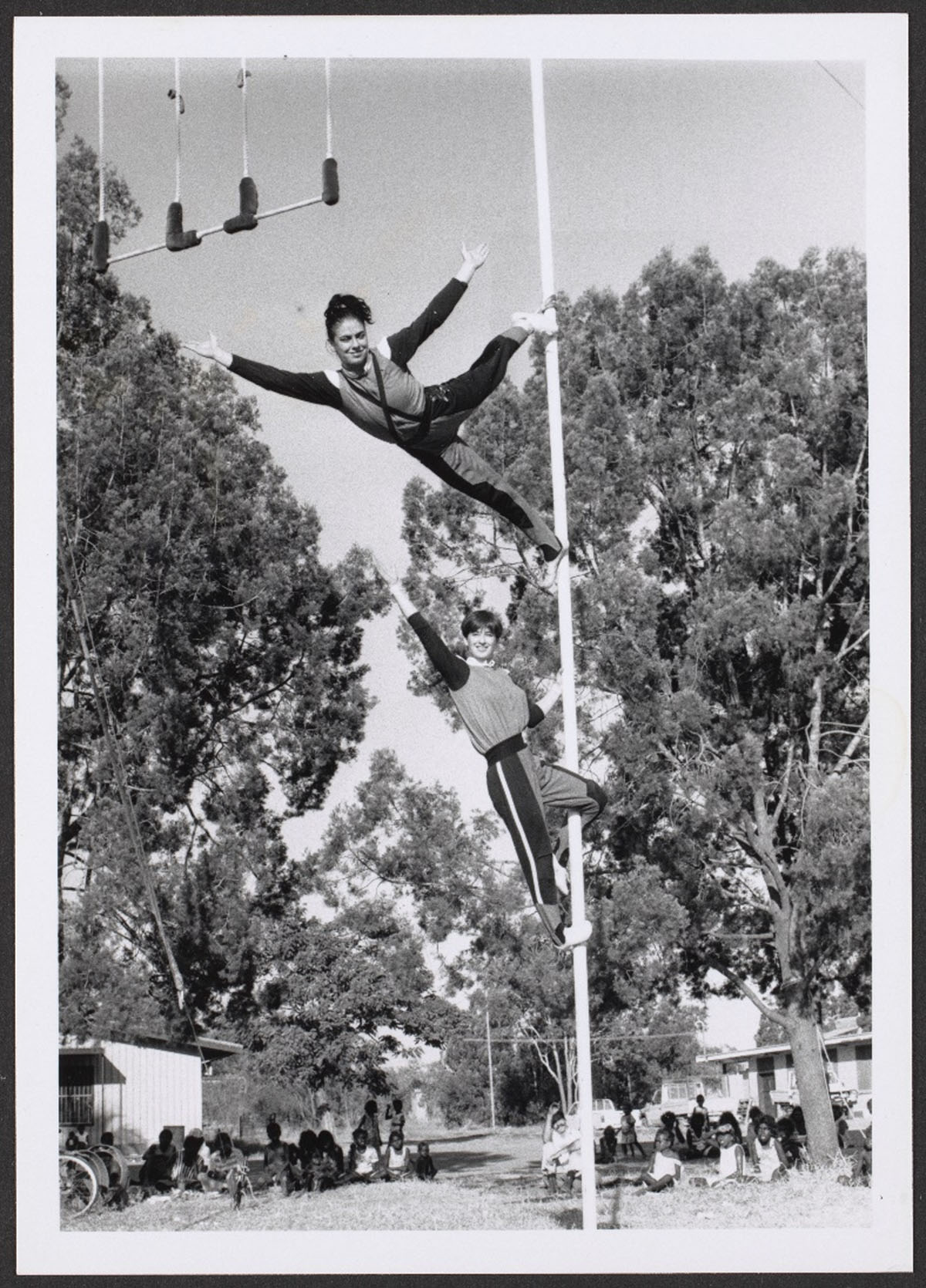

The video recording of a sunset performance at Uluru for the Mutitjulu Community on 16 August reveals a company lightly inhabiting the moment and place of the performance. A few mats sit on the red dirt on the edge of a lightly wooded area, surrounded by people sitting under trees at varying distances from the action. Behind the mats, a single trapeze is guyed off between two cars, forming a skeletal proscenium. The site is unpowered so the band performs acoustic, with additional percussion played on a chair and the side of a car. Acrobats and unicyclists veer comically through the space and into the audience, as if losing their sense of where the performance belongs. Gael Coulton on the trapeze appears spectacularly silhouetted against the darkening blue sky. Camp dogs wander around and incorporate themselves into the clowning. In one slapstick tumbling routine – called ‘The Knockabout’ – two performers hare off in pursuit of one especially gregarious dog, momentarily reducing the show into unscripted chaos. There are improvised dance numbers and even an unscheduled fire-swallowing act after the sun goes down.

Watching the remediated video documentation, one becomes aware of how much of the performance is not contained by the frame of the camera. The audience can be heard laughing and talking throughout the performance, even where no action is in shot, creating the uncanny impression that something has escaped documentation. It is also a reminder of how much the show, in this time and place, has deformed the traditional field of the performance. In order to follow the action, the camera must turn a full circle, suggesting that the audience has, in a sense, been enveloped by the circus ring. Audience members are coming and going, the performers are improvising up as they go along. In a sense they are unlearning or working against the centred structured performances that work so well for the company in majoritarian venues, such as the Variety Arts Theatre in Los Angeles. This is the counter-practice that they will extend on future tours to Arnhem Land.

The beginning of 1988 saw radical disruption of the national narrative when official Bicentennial celebrations were challenged by protests calling for recognition and justice for the dispossession of Aboriginal people. That year was also the tenth anniversary of the founding of Circus Oz and with increased arts funding from the Australian Bicentennial Authority the company were able to undertake a world tour, which included touring Northern Australia (Figure 5). With its grand-standing about tall ships and white men wearing uniforms and locking up convict settlers, the Bicentennial became an easy target for satire, which gave Circus Oz a chance to revisit their radical agenda for a broader audience. As a result, the new show featured a number of routines that questioned the national celebrations. This included the Bicentennial Re-Enactment, a sustained piece of clowning performed by Stephen Burton and Guy Hooper that culminated with Burton, representing ‘the forces of colonial invasion’, planting a toothpick flag on Hooper’s bum, representing the continent of Australia.4 Another politically-themed act, which was performed in all shows on the Arnhem Land tour, was the Bicentennial Rap. This featured a character called the Bicentennial Inspector for Gasbagging and Self-Congratulation who tries to censor the inflammatory content of the rap.

This political comedy, however, with its didactic and moralising content, was not a prominent feature of the Arnhem Land tour. The Bicentennial Re-Enactment, for example, was only performed in Yirrkala, the largest community. And yet the ways in which the form and content of the show was adapted for Arnhem Land communities does suggest a heightened awareness of and sensitivity to local performance conventions and their effects, which is not unrelated to the company’s critical attitude toward the complacent rhetoric of the bicentennial. The company, for example, invited collaboration in each of the communities in which they performed. In the 1988 show, Teresa Blake performed an aerial act accompanied by an orchestration that featured Anni Davey on the didjeridu. Before reaching Arnhem Land, however, the company received a letter insisting that a woman should not play the didjeridu because the instrument, known in East Arnhem Land as yidaki, is usually played in public by men. It would be disrespectful, insisted the author of the letter, if Davey played the didjeridu as part of the Circus Oz band. Davey accepted this advice and did not take her didjeridu on the tour. Instead, in each community, she invited a local musician to perform.

The recording from the 1988 Ramingining show reveals how this cultural exchange altered the rhythm and pacing of the performance. The show is an afternoon performance, and the company has set up next to a playground with a tall forest behind. A large audience has gathered, and children continue to use the play equipment while also watching the entertainment. About a quarter of the way into the performance, the show stops as the guest yidaki player, identified in the video only as Johnny, is introduced. The Bula’bula Arts Centre in Ramingining has helped us to identify the guest musician in this recording as John Gaykumanu. With their permission we have been able to name him, and recognise his music in this show, even though he has passed away.5 The introduction of Gaykumanu transforms the dynamic of the show, interrupting the seamless flow of acts, creating a moment in which the audience acknowledges its own participation. As he makes his way toward the stage from the back of the crowd, Gaykumanu pauses to say greet to members of the audience, shifting focus from the ensemble at the centre of the ring toward its periphery. Watching this unfold on video, it is possible to see in this moment of embodied performance, in the interruption of the frictionless transition between acts, the persistence of another order of circus expectations, rules and traditions.

Both the 1988 Arnhem Land tour and earlier 1985 Central Australia tour encouraged the company to experiment further with a performance practice in which the ring that delimits the performance area, that separates and divides, also selects and brings in. Company members were required to be alert to new connections, social and interpersonal, with those across the ring, and to the possibility of allowing them into the interior, into its centre, in the fragile unity of a common future. This heightened awareness of the potential for new relations of exchange and transformation was carried over on the 1993 tour. The Yirrkala show, for example, generates a festival-like atmosphere that further deconstructs the company’s practice. The company set up on the local sports ground with a view of the Arafura Sea behind them. A recording of the performance reveals a large audience in attendance, many families having travelled from the nearby mining town of Nhulunbuy. The edge of the oval is lined with cars and utilities. The show begins as the sun is about to set. After forty-five minutes of entertainment, young tumblers from the audience are invited onto the mats to show off their stuff under the lights while the band plays ‘Wipeout’. The video shows how the performance gradually transforms into a kind of fête.

At the end of the recording, which runs for more than an hour, children can still be seen taking turns climbing the poles and demonstrating their flips. The children have adapted the skills for their own play and performance. The show lights are still on, and Circus Oz performers are on hand to supervise. Similar scenes can be observed in the recording of the Galiwin’ku show from the same tour. The show finishes with local children performing tumbling routines on the Circus Oz mats. As darkness falls, legendary local band Soft Sands perform and turns into an inclusive dance party, the relations between bodies, time and space transformed.

Conclusion: Rethinking the Rings

In this paper, the image of the circus ring gives us a conceptual framework for understanding the role of databases, digital archives, virtual video libraries and mapping tools in tracing and theorising circus performance, and for interrogating the space of the circus. The new media potentiality of the digital archive copies the old media of earlier recording technologies but the researcher oscillates between the immediacy of viewing the reproduced event, and its hypermediality across multiple contexts and diverse ways of seeing (Bolter and Grusin: 19). Recognising the value of the performing arts archive as a distributed, transcontextual, interoperable resource (including digital artefacts and the data they generate), the significance of bodies, relations, and technologies converge and diverge across the intranational narratives of these Circus Oz tours. The combination of digital mapping, data curation and archival research has thus remediated the live performance and opened new perspectives on the history of Circus Oz in its emerging role as a national company.

Our research proposes a practice of reckoning through performance for the company in central and northern Australia: questioning their own practices, they were prompted to think differently about where they perform and for who. The exchanges taking place across this eight-year period modelled a performance mode that can be theorised as an ethics of intensive exchange. Performances in indigenous communities required the company to accept the renegotiation of boundaries and a dynamic of continuous movement, opening the shows to variation and chance interruptions. It also opened them to a recognition post-1988 that the company were performing on unceded, local arenas and ceremonial grounds that had their own long history of performance, artistic skill, and community involvement. The reworking of the theatrical assemblage for circus performances in these remote communities allowed for moments when the ring became more-or-less porous, creating the potential for new cultural, social and political exchanges.

These exchanges, which could not be predicted in advance, had ongoing material consequences for the company’s approach to the politics of the ring. One of the spectators at the 1988 Galiwin’ku show, for instance, Joshua Bond, has reflected on the significance of this tour:

They set up a tiny little show back then, and that had a massive impact on me […] that led on to me having a career in circus for 15 years. [The circus has] the potential to inspire other people from remote areas. I’m a living example of that. (Marks 2013)

After performing with troupes such as Queensland’s Circus Monoxide, Bond joined Circus Oz as an indigenous programs co-ordinator in 2011 and helped create BLAKflip, the company’s indigenous pathways programme.

Here we see how an interoperable series of research platforms has allowed new insights to emerge about the mobility of the circus: moving between global and local circuits, the immediacy of the event and the hypermediacy of the archive, and between settler and indigenous practices of performance. The research ‘ring’ (or field) re-conceptualises the performance ‘ring’, and both are put into question.

Notes

- This article is the first publication of the collaborative project Circus Oz: People, Places and Radical Exchanges (https://visualisingvenues.unimelb.edu.au/ppre/) led by theatre, dance, and arts management scholars at the University of Melbourne, and funded by the ARC LIEF LE210100007 AusStage LIEF 7: The international breakthrough. [^]

- Each digital object in TDP retains the same metadata identifying contributors (performers), location, venues and other description as well as the accompanying personalised narrative fragments ‘I was there, I wasn’t there’ but the collection also includes additional resources such as the full videos of a performance, photographs and other ephemera of the circus. [^]

- CIRCUIT was created for the Australian Research Council under Linkage grant LP160100047 Creative Convergence: Enhancing Impact in Regional Theatre for Young People. [^]

- In 1994, the critic and theatre historian Geoffrey Milne wrote that ‘In the 1988 show the circus’s skills and politics were were probably most effectively combined’ (35). [^]

- Bula’bula Arts Centre were provided with a copy of the video featuring John Gaykumanu. It was from this video that ‘Jonny’ was identified and permission was granted for the use of John Gaykumanu’s name for the purposes of identification in the archive and in related research. For more on Indigenous heritage repatriation see: https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/bringing-a-living-archive-to-life. [^]

Funding Information

Australian Research Council LIEF LE210100007 AusStage LIEF 7: The international breakthrough.

Ethics and Consent

Research conducted for this paper analysed existing data housed within public access archives and research repositories. Research drawing on secondary documentation was conducted ethically as per the guidelines laid out in the Australian National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research.

Images from Circus Oz are in copyright and have been published for research purposes only with the permission of Circus Oz. For information about reproducing these items or any part thereof contact info@circusoz.com.au.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that this article contains discussion of and links to video recordings that contain images and voices of deceased persons. Consent to identify and name deceased indigenous yidaki player John Gaykumanu was sought from and given by Bula’bula Arts in Ramingining, Australia.

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Author Information

Rachel Fensham is a Professor of Dance and Theatre Studies at the University of Melbourne and author of Movement: Theory for Theatre (Bloomsbury, 2021) and co-editor of the award-winning book series, New World Choreographies (Palgrave Macmillan). Her research and publications focus on theatre, dance, and digital humanities and she is currently leading the infrastructure project, the Australian Cultural Data Engine.

Andrew Fuhrmann is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne researching ambiance, mood and the communicative potentials of contemporary dance. He also works in the University’s Digital Studio developing the Theatre and Dance Platform, a repository of significant Australasian performing arts collections.

Kirsten Stevens is Senior Lecturer in Arts and Cultural Management at the University of Melbourne. She is the author of Australian Film Festivals: Audience, Place and Exhibition Culture (Palgrave Macmillan 2016), and co-editor of Screening Scarlett Johansson (Palgrave Macmillan 2019) and Transnational German Cinema (Springer 2021). Her research and publications focus on film festivals, screen industries, the histories of arts organisations, and digital humanities. She is a Co-CI on the Australian Research Council funded AusStage Lief 7 project (LIEF LE210100007).

References

Baston, Kim 2015 ‘“And now, before your very eyes”: The Circus Act and the Archive,’ in Performing Digital: Multiple Perspectives on a Living Archive, eds. David Carlin and Laurene Vaughan (Surrey, UK: Ashgate) 217–230.

Bench, Harmony and Kate Elswit 2016 Mapping Movement on the Move: Dance Touring and Digital Methods. Theatre Journal 68(4): 575–596. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/tj.2016.0107

Bollen, Jonathan 2016 Data Models for Theatre Research: People, Places, and Performance. Theatre Journal 68(4): 615–632. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/tj.2016.0109

Bolter, Jay David and Richard Grusin 1999 Remediation: Understanding New Media Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1108/ccij.1999.4.4.208.1

Boussiac, Paul 2012 Circus as Multimodal Discourse: Performance, Meaning, and Ritual. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Burdick, Anne, Johanna Drucker and Peter Lunenfeld (eds) 2012 Digital_Humanities, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9248.001.0001

Carlin, David 2015 ‘Time and Narrative in the Digital Archive: On Account of a Circus,’ in Performing Digital: Multiple Perspectives on a Living Archive, ed. David Carlin and Laurene Vaughn (Surrey, UK: Ashgate) 13–28.

Greaves, Geoff 1980 The Circus Comes to Town: Nostalgia of Australian Big Tops. Sydney: Reed Books.

Lury, Celia 2021 Problem Spaces: How and Why Methodology Matters. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Marks, Lucy 2013 Circus Oz’s tent is wide open for indigenous performers. Sydney Morning Herald 29 December, pg. 3.

Milne, Geoffrey 2004 Theatre Australia (un)Limited: Australian Theatre Since the 1950s. Amsterdam: Rodopi. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1163/9789004485839

Mullet, Jane 2015 ‘Circus Oz: A Reflection,’ in Performing Digital: Multiple Perspectives on a Living Archive, ed. David Carlin and Laurene Vaughn (Surrey, UK: Ashgate) 201–21. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315599960-21

Russell, Lynette 2005 Indigenous Knowledge and Archives: Accessing Hidden History and Understandings. Australian Academic & Research Libraries, 36(2): 161–171. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/00048623.2005.10721256

Tait, Peta 2005 Circus Bodies: Cultural Identity in Aerial Performance. New York: Routledge. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780203391303

Thomas, Martin 2011 ‘Expedition as Time Capsule: Introducing the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land,’ in Exploring the Legacy of the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition, ed. Martin Thomas and Margo Neale (Canberra, Australia: ANU Press) 1–30. DOI: http://doi.org/10.22459/ELALE.06.2011.01

Varela, Miguel Escobar 2021 Theater as Data: Computational Journeys into Theater Research. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P.

Vaughan, Laurene 2015 ‘Performance, Practice and Presence: Design Parameters for the Living Archive’ in Performing Digital: Multiple Perspectives on a Living Archive, ed. David Carlin and Laurene Vaughan (Surrey, UK: Ashgate) 75–87.