Ten in the morning is not the most usual time for a press view to open, nor is the requirement to show ID and Vaccination Pass, but at the Palazzo Cipolla (lit. ‘Onion Palace’) on the Corso del Rinascimento in the centre of Rome, this was the routine to see an intriguing show of work by David Quayola, an Italian digital artist, long resident in London, but here displaying a variety of pieces made over the last fourteen years. Suffice to say there was not an ice filled dustbin of Peroni bottles in sight.

Born in 1982, Quayola is of a generation of artists for whom digital processes are not just an adjunct to his original metier, but have been his principal means of creation from the beginning. As a consequence, not only do his works have a polished and visual fluency which eludes many others but they are all demonstrably his – not the products of some phantom army of ‘fabricators’, of whose existence the artworld keeps to its own code of omerta when it concerns big reputations.

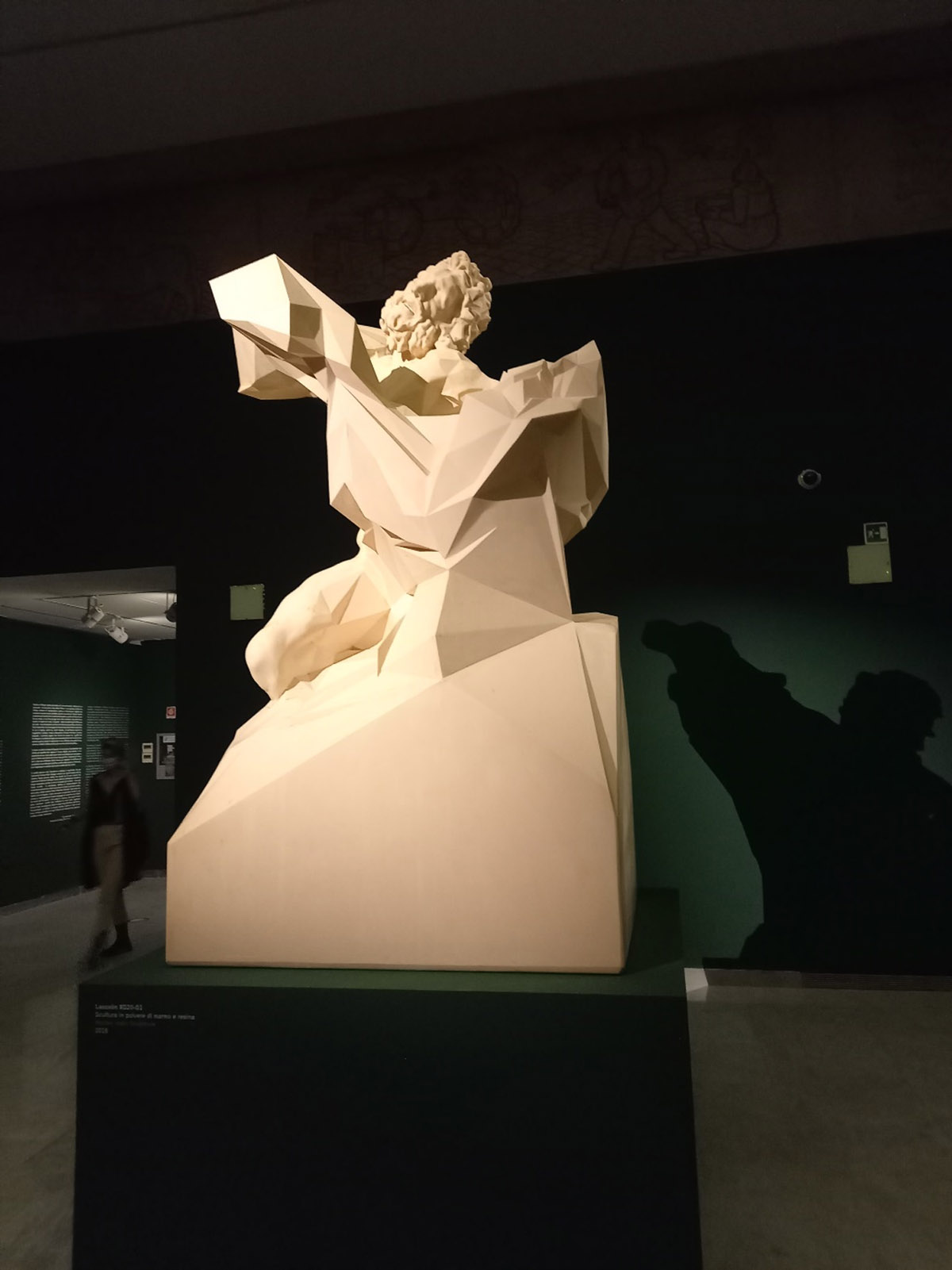

At the centre of the show are a series of digital flat works and sculptures which take as interpretive material some virtuosic pieces of antique and baroque art. These are then subjected to a reworking generated by elaborate coding, which results in an overlaying of, and interpolation within, the original. ,a formalistic visual language, owing something to cubism and suprematism, but which possesses a compelling quality that saves it from the predictability so common to digital work that makes use of a similar vocabulary. Such recensions of history are quite current; as it happens, on the same day as this press view, a semi-retrospective show of Jenny Saville’s work in the same vein opened at several sites across Florence. But Quayola opposes his raw material with a far starker vocabulary, and allows these processes to run their course, even if the results can end up being somewhat hermetic.

Davide Quayola. Video Clip. Strata 4#, 2011. Susan Broadhurst, 29th September, 2021.

He also varies the transformations themselves. Another series of works on the show employ programs referencing Impressionism and Neo-Impressionist Pointillism, overlaying landscape sources. Some of these screen-based pieces enact their own creation, much like an accelerated visual narrative of how a painter would work, be it Monet, Seurat, or Signac.

Davide Quayola. Video Clip. Jardins d’Été, 2017. Susan Broadhurst, 29th September, 2021.

His sculptural works imprison digitally produced fragments of the Laocoon group (that centrepiece of the Vatican Museums’ sculpture court) enclosed by modernist devices., in a way, which could be reminiscent of Michelangelo’s unfinished ‘carceri’, but with more originality than mere evocation.

This is a show which deserves attention beyond Italy, and, when briefly talking to the artist, I was surprised to learn that, when in London, he was not represented by a gallery (perhaps an indicator of the implicit narrowness of tastes there). I look forward to seeing where his next directions lie. Perhaps the future will entail the abandonment of historical anchorages altogether. I am repeatedly prompted to think that the early proposals of modernist theorists were ahead of the technological means to realise them. It may be that such an accomplished use of what we now have at our disposal, will result in a revisiting of that era which, in effect, owes little to it. We’ve had Po-Mo, so how about Metamodernism?

QUAYOLA re-coding, Palazzo Cipolla, Via del Corso 320, Roma, 29.09.2021–30.01.2022.

Acknowledgements

Photos by Sue Broadhurst.

Author Information

Neil Harvey is an artist and writer on art. He is based in Fivizzano, Tuscany. He is deeply interested in issues arising from nineteenth century German aesthetic theory.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.