A late friend of mine once reviewed new poetry collections. He stopped after a while. He told me ‘I just ran out of things to say … the words evaporated’. I know how that feels. This Biennale seemed designed to resist easy verbalisation, not because its contents were in some way hermetic or even apophatic, but because any commentary would seem to address anything but its ostensible intention. For the avoidance of doubt, as lawyers say, the Architecture Biennale is, presumably, meant to be about contemporary architecture worldwide. Architecture is, by definition, the making of structures and their surroundings that enclose, shelter and/or protect a multiplicity of functions. Of course, the wider purposes in such making, and the effects it has on societies and the environment, are of an importance that cannot be ‘bracketed off’ (Epoché), to use Husserl’s phrase, from the formal qualities of what is made (1989). But without some consideration of the latter, the rest is more of sociological interest than aesthetic.

The 2023 Biennale had the overall title ‘The Laboratory of the Future’, which might imply that we were going to see, in some way, buildings of the future. If that was the expectation then we were going to be generally disappointed. In his perceptive review, published in Art Review in July, Joe Lloyd remarks on how there were so many artists in other disciplines included in this Biennale, ‘you might be forgiven for wondering if it had swapped editions with its older sibling’ (2023). He continues ‘Many of the contributions by architects bear little relation to their buildings, instead favouring conceptual works on subjects as varied as decolonisation and the value of soil’ (Lloyd, 2023). I couldn’t put it better myself. Now far be it for me to concur with anything else that Patrik Schumacher, Zaha Hadid’s controversial successor, has said, but, as quoted by Lloyd, he nails it completely for me: ‘The Venice “Architecture” Biennale [his scare quotes] is mislabelled and should stop laying claim to the title of architecture. Assuming Venice to be not only the most important item on our global architectural itinerary, but also representative of our discourse in general, what we are witnessing here is the discursive self-annihilation of the discipline’ (Lloyd, 2023).

So, have I just broken the first rule of reviewing, stating my general conclusions before even addressing the subject? Well, the problem is, this sense of irrelevance was so strongly apparent whilst touring the shows, it is almost impossible to recall the content of these in a disinterested manner. But, within the limits of what I could see, I will try a severely edited tour.

Taking the familiar clockwise circuit of the Giardini Pavilions, Spain exhibited ‘Foodscapes’, graphicky mood boards and films, exploring the global food supply chain, but not what might have been the more adjacent matter of kitchen design. Belgium offered a fibreboard enclosure covered in mycelium fungus, as proposal for a future building material. The Netherlands revived the 60’s pre-computerised notion of building a water-circulating model of the economy.

The old Central Pavilion divided between a project for mentoring young architects, and a retrospective of Demas Nwoko, recipient of a 2023 Leone d’Oro for Lifetime Achievement.

Hungary showed a cuboid projection associating a recently opened Budapest museum with music. Israel simply sealed up its pavilion, to ‘define the transition from analogue to digital in communication technology’. The Venetian pavilion took a rare excursion into relevance by showing new renewal projects for Mestre and other outlying districts. Serbia featured, bizarrely, a trade fair building in Lagos. Poland had a coloured climbing frame symbolising the ‘material result of data processing’. Romania hosted Romanian inventions, including a 1904 electric car. Greece showed reservoirs. Uruguay examined its burgeoning forestry industry. France had a sound stage system. Germany, a load of building materials. The USA commissioned artists to design plastic installations. The Canada Pavilion was occupied by the Architects Against Housing Alienation.

The long hall of the Corderie (ropeworks) of the Arsenale usually holds some of the most ambitious works in any Biennale. This year it was divided between 37 architecture practices under the title ‘Dangerous Liaisons’. I only wish they could have been really dangerous, in which case I could have remembered them in detail. As it was, it seemed to be a succession of foyer-standard displays which slipped by without impression. And, I have to admit, the same went for those national pavilions already open to the press, in the remainder of the Arsenale.

It will be apparent that this Biennale consisted of a huge variety of intellectual digressions, none of which could be called fascinating. There was an overriding and introverted concern with what might be called the sociology of the profession. And it must be clear that the visual presentation of, at least, good architecture, and its sense of spectacle, was entirely absent.

Here I have to remove my reviewer’s hat and attempt to offer remedies. The Architecture Biennale has no future if it continues, like the Israeli pavilion, to ignore its central concern and chooses exclusively a periphery of related issues. I think this may stem from that elephant in the room, the present standing of the architectural profession. The few ‘starchitects’ attract the appreciation of the mainstream media, but on the whole, architects have an elephantine image problem. They are generally regarded as the arrogant, overpaid corporate lackeys of dubious commissioning entities, whether state or commercial. Their talents are often not conspicuous. I know architects, as I know lawyers, to whom such stereotypes are inapplicable. The Biennale at present seems to display some awareness of this, and so offers, as a whole, wan, diversionary PR, showing how concerned the profession is nowadays with sociological, green and inclusive matters. It should instead confront this image problem directly. It needs some shows with the subtext ‘yes, we know we’re hated’. It should possibly have its own ‘pavilion of infamy’ to illustrate the worst examples built since the last one (that may not go down too well their respective national pavilions). It should readily acknowledge its complicity with those who abuse their wealth and power. In other words, get in touch with its dark side…

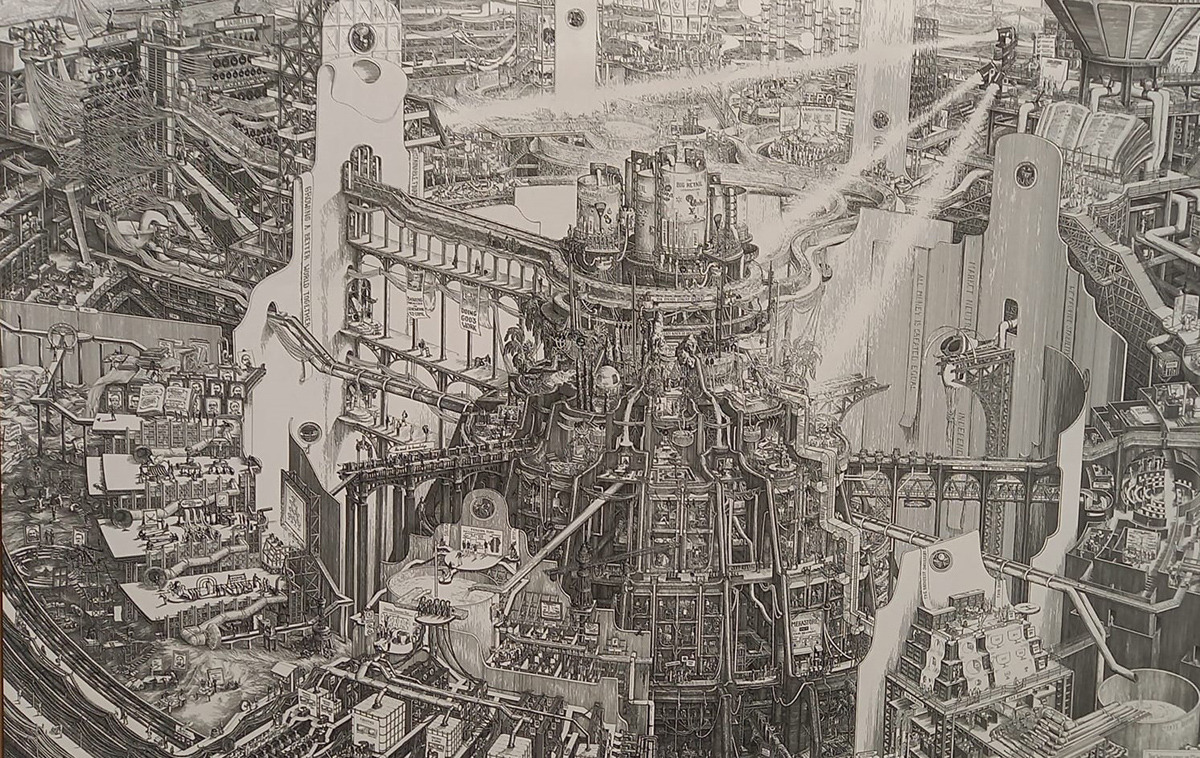

The other task the Biennale could give itself is educational. Very few of us have much idea how contemporary buildings are constructed, both in process, materials and result. The little knowledge we have dates from, most recently, the ‘60’s and before. Presumably things have got much more sophisticated and eco- since then. Perhaps it is because the Biennale seems to be introvertedly addressing its own profession, but there is no attempt at present to offer intelligent explanations of modern building practice. Again, perhaps this is a consequence of the larger practices having distinct engineering departments who take care of these things independently of the architects per se (which has raised the question recently in the press of how ‘in touch with materiality’ architects are nowadays). In any case, it might seem college-level stuff for the profession (and perhaps it is knowledge some of them wish to reserve to themselves), but it would be an attractive subject for displays to enlighten a lay audience.

Finally, what struck me most about the displays this year was how limited and unimaginative were the resources for demonstrating the few real projects it featured: some of the usual grey models with matchstick trees, some still images and a few videos. In an age when, I believe, architects habitually compose in VR, why were immersive forms of this not being used to approach the experience of physically engaging with architecture? So many projects nowadays seem to produce their own VR showreel using precisely these technologies. It is a mystery as to why a presumably adequately-funded Biennale had, I seem to recall, no examples of them. It is surprising that the profession apparently has so little sense of how to make spectacles of its creations.

And so… that, I think, is our last Architecture Biennale for now. If it, as it were, rebuilds itself, then we might reconsider. But Schumacher, whose general opinions I abhor, is right here, if this ‘self-annihilation’ continues there won’t be anything left to see, just a few ‘discursive’ labels (Lloyd, 2023).

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Author Information

Neil Morris Harvey is a freelance artist and sometime writer who lives in Northern Tuscany.

References

Husserl, Edmund 1989. The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology: An Introduction to Phenomenological Philosophy. Translated by David Carr. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Lloyd, Joe 2023. ‘How Architects Fell Into Bed With the Artworld’. Art Review Available at https://artreview.com/how-architects-fell-into-bed-with-the-artworld/ Accessed, 5th November 2023.